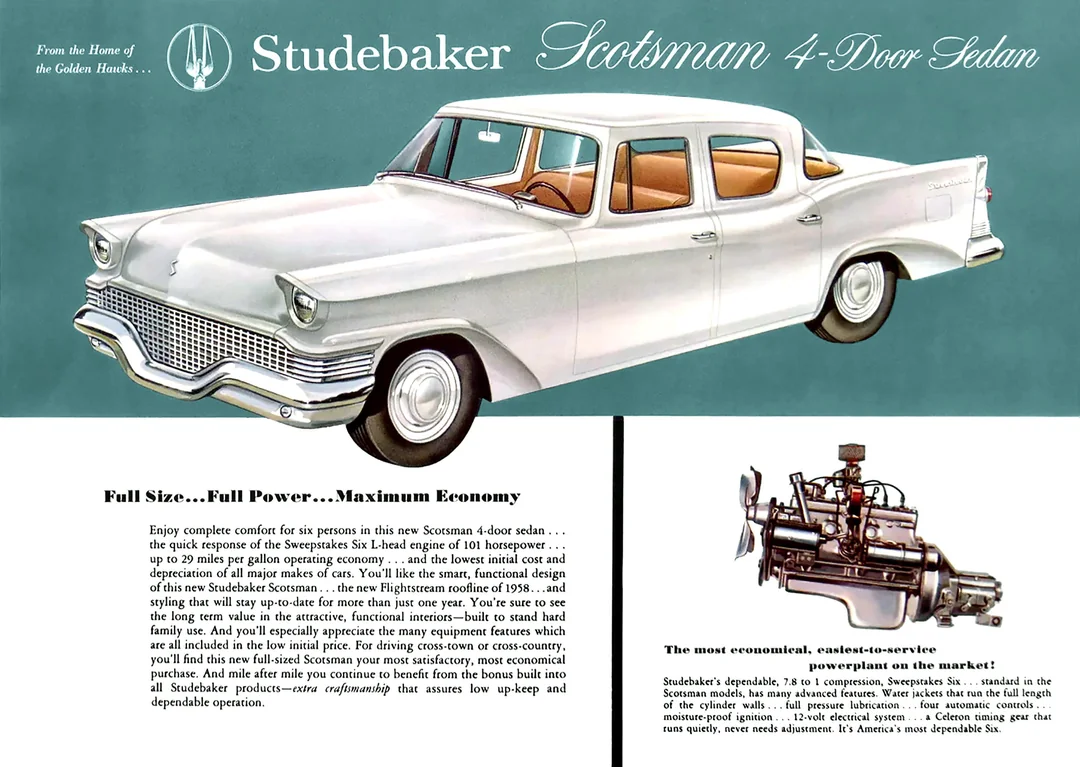

In the pantheon of base models, the Studebaker Scotsman is truly the patron saint. In the era of chromed-up Detroit dreamboats, the Scotsman had painted cardboard door inserts and even a proper heater cost extra. That chrome strip on the side is a rare show of excess on one of these. Created purely as a way to build volume — it worked. In 1958, the Scotsman was the most popular Studebaker.

As most readers will already know, Studebaker was in deep, deep trouble financially by 1957. Its management was searching for any possible method of increasing sales volume. Cheap cars have razor-thin margins, but the more you build, the lower the unit cost of each one. In 1954, the newly merged Studebaker-Packard had hoped to have all new bodies ready for 1957, but when the company lost $26M that year, cost-cutting measures were the order of the day. Studebaker never again produced an entirely new car, and in the short term, it had to make do with what it had.

What became the 1956-58 Studebakers (and the 1957-58 Packards) were really just heavily reworked versions of the low-slung 1953 models. The 1956 exterior restyling was mostly done by Vince Gardner, who worked in a warehouse almost alone for months while S-P cut costs. The company’s long-standing design contract with Raymond Loewy & Associates and Ed Macauley, Packard’s design chief, were two early casualties of the company’s cash-flow crunch.

Duncan McCrae & Studebaker’s Late Design Staff

To help Gardner, Studebaker hired industrial designer Duncan McCrae in mid-1955. His first job was working on the interiors of these new cars, but he later speculated that the design staff decisions happened in early 1955, before he joined, and that he was always intended to do more. By the end of 1955, S-P had lost $30M. McRae had the unhappy task of winding down and laying off the Loewy staff, including Bob Bourke, the man who had designed the ’53 Studebakers on which the ‘56s were based. Bourke’s ’56 Hawk updates were kept.

Theoretically, these newly-styled cars would serve two years before a whole new platform, envisioned by CEO Jim Nance, could underpin all-new Packards and Studebakers. The cost of that car was projected at $50M. It was not to be.

The restyled cars (a frequently underrated design) looked fresh even if they were not truly new, but Studebaker sales continued to fall, seriously eroding the company’s dealer network, cash flow, and ability to keep making cars at all. By the end of 1956, Studebaker-Packard’s losses had risen to $100M. In July of that year, Curtiss-Wright stepped in to rescue the company, and Nance departed. Curtiss-Wright appointed chief engineer Harold Churchill to replace him.

Make it up on Volume

Curtiss-Wright then bet the company’s future on Studebaker’s ability to build a break-even volume of cars rather than trying to make big profits on low-volume Packards. By then, there was no way to develop a whole new car, and Gardner and McCrae worked tirelessly to keep the ‘53 cars fresh as other designers (like Packard’s Dick Teague, who defected to Chrysler and then American Motors in 1959) departed one by one.

Since 1939, Studebaker had offered a value-leader car in the form of the Studebaker Champion. The original Champion was a relatively small car and separate from the senior Studes, but after 1947 Studebaker used one platform in various lengths. The Champion remained as the value Stude, pitched against the low-end cars at Chevy, Ford, and Plymouth.

Starting in the wake of the Korean war and the loosening of credit terms, Ford and Chevy had crushed cheap cars from independents and there was no way Studebaker could fight their economies of scale. The Champion declined with buyers lost to the Chevy 150 and Ford Custom, but there was still a value customer. Rather than adding features or styling flourishes, which cost money and production time, in early 1957, Churchill and company decided that there was room for a car beneath the Chevy 150 or the Champion.

By removing features and charging a lower price, Studebaker could build more cars. The new “stripper” model would have tiny profits, but it would lower the unit cost for more profitable cars while costing almost nothing to add to the line.

The Studebaker Scotsman

First, let’s get past the name. “Scotsman” was chosen to invoke the problematic stereotype of Scottish thriftiness, which was neither accurate nor fair like all stereotypes, but this was 1957. Chrysler also had a low-end model in the early 1950s called the “Highlander” that had similar connotations. Today’s Toyota Highlander seems neither grounded in this idea nor the adventures of Conner MacLoed, but that’s an aside.

The car wouldn’t be an entirely separate model but a subset of the Champion line — the “Champion Scotsman.” Management deleted and deleted pieces of the regular Champion until it produced a $1776 2-door sedan and slightly costlier (but still super cheap by mainstream 1957 standards) 4-door and 2-door wagon variations.

The Scotsman came only with the old 101-hp Champion flathead six (not so different from when it first appeared in 1939) and a 3-on-the-tree. Power accessories? None. It had mostly painted metal trim rather than chrome (shades of 1942’s “Blackout” cars). The interior was austere in the extreme—vinyl benches, painted metal trim, rubber floors, cardboard door inserts and trim pieces. Cardboard!

All this made it cheaper than any Chevy, cheaper than a Hillman Minx (a popular import that, thanks to the involvement of Loewy & Associates, looked sort of similar), and only $250 more than a VW Beetle, which was just as basic inside, foreign, and small.

Though out of step with the “fabulous” decade, it was well timed – the “Eisenhower Recession” in 1957-58 sent buyers scrambling for low-priced cars. The Scotsman added 10,000 sales to the Champion line in ‘57 and was 1958’s most popular Studebaker, with almost 21,000 sold. It also helped get buyers in the door — lured by the low price, more than one customer moved up to a plusher Champion or Commander when they saw the equipment list (or lack thereof). The Studebaker Scotsman also got at least once celebrity endorsement — former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt bought one and loved it.

The ‘58 Scotsman did without most of the cosmetic updates of the other 1958 Studes (such as the tacked-on tailfin extensions and quad headlight pods) to keep the price low. Volume was also boosted by creating various fleet products out of the stripper, including the Econo-o-miler taxi and police specials. It was rare, but for a fleet customer, Studebaker would build a stripper Scotsman sedan with its potent V8.

Wagons were 2-door only, a configuration that was still popular then but quickly fading. They were aimed at utility customers and some got metal panels to make them into sedan deliveries. Though Studebaker finally added a four-door wagon in 1957, it wasn’t available as a Scotsman.

The car helped bridge the gap to the ‘59 Lark, another budget-minded mashup of the ‘53 platform (South Bend could not afford something entirely new) designed mostly under McCrae.

We spied two of the cars pictured here, the ’57 Scotsman wagon and the ’57 President, at the Ron Hackenberger auction in 2017.