It was the summer of 1995 and finally, a new Alfa Spider had arrived – at least for Europeans.

After 27 years, the last of the old 105-series Spiders rolled off the line in April of 1993, making way for an entirely new kind of Spider and, for the first time since 1974, a related GTV on the same platform. The pair first broke cover in Paris in late 1994, but they’d been in the works for a long time by then.

The following spring, the two cars went on sale and were immediately popular with Europeans. Sadly, Alfa had thrown in the towel on North America just a few months earlier. You could still buy an Alfa for a few months, but the Spider and GTV were not going to be federalized. All U.S. Alfisti could do was watch Europeans enjoy the new Spider, a style standout, but one that arrived too late.

Tipo 916 and its Origins

The “Tipo 916” Alfas, the Spider and GTV, looked radically new at the Paris show, but their lines had been signed off on many years earlier. Their lead designer, Enrico Fumia, penned them in 1987-88, and they incorporated styling cues that dated back to 1980 and another Fumia-penned Pininfarina car, the Audi Quartz (a one-off rebodied Audi Ur-Quattro).

Alfa had long wanted to replace the old 105-series Spider, of course, but never had the money or time to really do anything about it.

In the 1970s, labor and economic problems hobbled the state-owned automaker, a part of the Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale (IRI) since 1933. In the 1980s, the only way it could properly replace its existing platforms was to partner with other manufacturers.

One such partnership, with Nissan, led to the forgettable ARNA. Another was Alfa’s entry into the “Type 4” project along with Fiat and Saab, which led to the 164.

So the Spider, which continued to sell in small but reasonable numbers (mostly in North America) got to remain. But work really began on casting around for a new direction in 1985, shortly before IRI, by way of subsidiary Finnmeccanica, sold off Alfa to Fiat late in 1986.

Earlier that year two of the first previews of what would become the Spider and GTV were shown to the public at the Turin show – the Alfa Vivace concepts. The Vivace did away with the sharp-edged, origami looks of Alfa’s chief designer Ermanno Cressoni and were instead done (at least according to most sources) by Enrico Fumia and Diego Ottina at Pininfarina.

The cars only lightly referenced Fumia’s earlier Quartz concept, but they had gentle, slab-sided lines with a sort of Alfa 164-esque front end, not surprising since the 164 was being worked on by the same team at the time.

Alfa intended that both a Spider and a Coupe would be forthcoming to replace the Alfetta GTV/GTV6 and the old Spider, but there was no money for them at the time. Nor were there any new platforms in the works and reworking the Alfetta one more time was a non-starter. The only thing Alfa had in the pipeline was the 164.

In late 1986 Fiat bought Alfa, and suddenly Alfa Romeo had access to Fiat’s upcoming platforms. Aside from the 164, It would be a good long time before a Fiat-infused Alfa came to market. But now there was a way forward.

Unlike the old Spider, the new one would have to fit into Fiat’s cost and engineering structures, and the person overseeing both was Engineer Vittorio Ghidella.

Vittorio Ghidella & Fiat

Ghidella had been appointed by Gianni Agnelli to run Fiat Auto in 1979 at a time when Fiat was really struggling with labor and quality problems as well as dated or overly conservative products.

Born in Vercelli in 1931, Ghidella’s first job after graduation from Turin Polytechnic was as a timekeeper for Fiat and a manager of piece-work workers. He was an engineer and a manager and excelled at both – eventually departing Fiat for SKF ball bearings, where he rose to CEO before Giovanni Agnelli poached him back to Fiat. In the 1970s, he briefly ran Fiat-Allis tractors before being asked, again, to help out with cars.

In 1979 Fiat was not exactly in the same situation Alfa was in 1986, but the pipeline for new products was weak. The only really new thing Fiat had in development was the Mk1 Panda, a Ghidella project. Ghidella’s turnaround focused on new programs in the purposeful mode of the Panda and the first of these was the Fiat Uno.

Foremost, Ghidella understood cars and loved them – many of Fiat and Lancia’s most popular cars of the 1980s – the Fiat Uno Turbo, the Lancia Delta Integrale, etc., were created under his watch and with his encouragement.

No car from that period was more important than the Uno, the single most successful Italian car of all time and a vast well of profits for Fiat. It was not exciting to look at, but did everything well, and focused intensely on value for money. Released in January 1983, its success paved the way for the next round of Fiat’s engineering projects, including another new platform – Project 160, which became the Tipo.

Already well along by late 1986, the Tipo, Ghidella and his managers decided, would be the basis for the new Spider and GTV. That would mean a radically different car than any previous Alfa sports car, as only the cheap-and-cheerful AlfaSud and its derivatives had been front-drive up to that point. But it also allowed for a new platform in a cost effective way.

Indeed, the Tipo – European Car of the Year in 1988 – would be one of Fiat’s most valuable platforms and spawn many models at Alfa, Fiat, and Lancia. It would be known internally as Fiat’s “Type Two.” A larger version, which would underpin the Fiat Tempra, was called the “Type Three.” Both would serve Fiat well for a long time.

The exterior of the Spider and GTV, done primarily by Fumia, was locked down by mid-1988 and development of the mechanical pieces underway.

But despite record profits and having built Fiat Auto into a powerhouse, a rift formed between Ghidella and Fiat SpA’s CEO Cesare Romiti when Ghidella went around him to the Agnellis directly with an idea for a new city car.

The Tough Guy

The blunt-talking Romiti was known as Il Duro – “the Tough Guy.” In 1974, when Fiat was thrown into chaos by OPEC, inflation, and massive political and economic turmoil in Italy, Giovanni and Umberto Agnelli had asked him to come in and help. The head of Alitalia at that time, he was recommended by Italian finance kingpin Enrico Cuccia of Mediabanco.

The Agnellis had little choice, and Romiti was horrified by their books. He soon laid off thousands of employees, a deeply unpopular move at the time. But Romiti was like the tide – a force not to be denied. He had a way of bending Fiat’s Unions to the will of the company even in a time when wildcat strikers in Italy periodically assassinated executives like himself and politicians alike.

His lack of fear may have gone back to his youth – his father was dismissed from the Italian postal service for being anti-fascist at a time when that was physically dangerous. Later he stole food from German military depots during WW2.

Romiti was tough as nails and a trained economist. He could make the books work and the workers too. He even managed to help secure a major cash injection for the company from, of all places, the Government of Libya. But he was not a car guy, and Ghidella was promoted to make the actual product compelling.

A year later, in 1980, Romiti had taken over much of the operational control of the entire company. That same year, he helped unwind a major strike that he alleged had been the work of the Red Brigades, a violent communist group – that earned him major league political capital with workers and the Agnellis.

Ghidella’s products were excellent, but Romiti could not abide a challenge to his authority – and the two regularly clashed. It was rumored that Umberto Agnelli strongly supported Ghidella to become the next CEO, and that Giovanni Agnelli might also want that outcome. At that point, it became a power struggle.

There was more to it – Romiti wanted to cut costs and diversify. Just like Roger Smith at GM, Romiti invested heavily in developing non-Automotive interests for the company (unlike Smith, they were often successful); Ghidella was the head of the automotive part of the company and wanted efforts concentrated there.

The project that put the situation over the top was Ghidella and Umberto Agnelli’s plan to build a tiny car that might be sold as a Piaggio, a brand more associated with scooters and the tiny three-wheel Ape truck. Romiti was incensed that Ghidella had worked with Agnelli directly and hounded him out. The final fight happened in a boardroom in July, and Ghidella resigned in November.

Romiti temporarily replaced him and while a good administrator, his approach was cost cutting in every area. Various projects that should have been finished in 1991-92 dragged on as a result of the shuffle, including the Spider and GTV.

Ghidella’s little car? It was enlarged and ended up as the Fiat Cinquecento in 1991. Ironically, it was styled by Ermanno Cressoni, the origami-lined Alfa guy.

Tipo 916 Comes to Life

Despite all this turmoil, the Tipo was an unqualified success and Alfa’s engineers, including Lancia’s Bruno Cena, built the car into an excellent trio of models. The First was the Alfa Romeo 155, based on the slightly larger “Type Three” bits, and then the Spider, GTV, and the hatchback 145/146 on the “Type Two” architecture.

The engineers built a responsive driver around Fumia’s daring styling. There were also many production changes to ensure better quality and better rust proofing than older Alfas, and the new Spider did prove more robust.

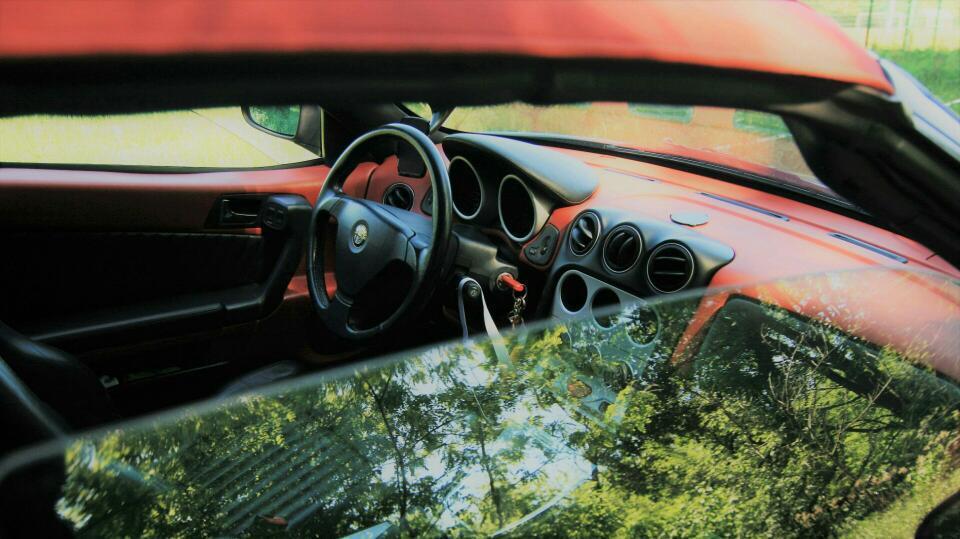

Initially it was offered with the new Fiat-based 2.0L 16V “Pratola Serra” twin-spark four and the Busso V6. Exciting to look at and to drive, the Spider was far less rigid than the GTV, but both Tipo 916 cars were popular.

It was the GTV which got most of the performance cred, and was one of the best front-drive sports cars of that era. In the words of EVO, “It’s hard to think of another £30K car you’ll lust after in the same way.”

Although the 155 was the first post-Fiat Alfa, it was a family car first (though there were plenty of sporty versions) and it was the GTV and Spider that really ignited honest sports car passions for Alfas. In the late 1990s the brand seemed to go from strength to strength, with the very well received 156 replacing the 155 in 1998.

Americans, by far the biggest market for the old Spider, never saw any of this. The Tipo 916 cars went on sale in the spring of 1995, by which time Alfa Romeo’s American and Canadian fortunes had sunk pretty low.

After Fiat bought Alfa Romeo, it invested a little bit more in Alfa’s U.S. operations and changed up the management. Then it partnered with Chrysler to form a new distribution organization in 1989 – Alfa Romeo Dealers of North America (ARDONA), which got access to Chrysler’s network. But then came the Gulf War recession and the relatively lackluster sales of the 164.

When the 164 had been launched ARDONA had plans for selling as many as 30,000 a year in North America. Alfa sold 3,478 cars in the USA 1991, a chunk of which were 105-series spiders. Chrysler walked away from ARDONA in 1991.

Talk of the new Spider didn’t stop, but in the summer of 1993 Alfa Romeo decided not to make the huge number of modifications it would need to make the Spider U.S.-compliant. The same year it had decided that the 166, due to replace the 164 in 1996, would also not be coming stateside.

With no old Spider to sell in 1994, just 565 Alfas were sold for the whole year in the USA. In February, 1995, Alfa decided to shutter its U.S. operation entirely. It directed foreign efforts to Japan, instead, where Alfa sold eight times as many cars a year.

This did not mean that U.S. enthusiasts didn’t stop trying to get new Alfa Spiders, however.

Starting in 1990, any car under 25 years old had to be certified DOT and EPA compliant – a hugely expensive proposition. Several companies tried to certify the Spider and GTV for US sale in the late 1990s and a few were brought in through questionable channels. It’s possible to bring in a car and license it “under the radar,” but if you’re caught, there’s a good chance your brand new car will meet an untimely end with a crusher.

In Canada, where rules for very low volume imports were a little less strict, the Spider and GTV gained a following much sooner. It’s only now in 2020 that Americans can enjoy the early Tipo 916 Spiders and GTVs legally.

Ghidella was immediately picked up by Ford when he resigned, but Fiat sued Ford into not using his services. Instead, he moved to Lugano, Switzerland, after leaving Fiat and was the CEO of busmaker Soarer until 1993; later becoming involved in venture capital. He died in 2011.

Romiti remained a powerful part of Fiat until 1998 – but a year earlier he had been found to be part of the Tangentopoli scandal, a broad ranging investigation of political corruption in Italy. Romiti went on to a lavish retirement, but not before being found guilty of tax fraud and illegal political contributions. He died on August 18, 2020.