It lasted for just 12 months, and in that time, only 1,255 found homes, but you can’t say BMW didn’t give it a chance. The BMW 1600 GT was, arguably, born on November 10, 1966 – the day BMW acquired Hans Glas, GmbH in a big ceremony in front of 4,000 soon-to-be BMW employees at Glas’ Dingolfing factory.

Many of those workers were worried BMW would shut the plant and turn it into an R&D facility, but Munich promised to continue the production of Glas cars, at least for a while and they would. The idiosyncratic, notably tight-fisted, and then 76-year-old Hans was there himself that day, and he too had fretted that his workforce – ramped up steadily over the previous two decades – would suffer in the deal.

In the end, the factories were more than safe. BMW not only kept Glas’ Dingolfing plant and Landshut side operation going, it eventually expanded and replaced them with much bigger factories. Glas’ technical expertise was absorbed too – directly informing future generations of BMWs, starting with the 2002 Touring.

BMW could have killed off the Glas cars and name right then and there, but it didn’t. Instead, Glas’ last designs rode out their cycles in a blaze of glory as BMW modified them and marketed them as BMWs.

There were two, both with bodies styled by Frua in Italy. The larger one was the Glas V8, sometimes called the “Glaserati” for its overt resemblance to Frua’s Maserati Quattroporte design. The smaller one was the BMW 1600 GT, formerly known as the Glas 1300/1700 GT. It’s that car that you see here.

The Glas V8 got only minimal changes before the BMW badge was applied, but Munich seemed to really want to make the GT its own. It was already four years old, but BMW lightly restyled it, added its own engine, 12-volt electrics, and gave it a new rear suspension. It was already a good car, but BMW’s changes made it a great one. The first BMW versions rolled off the line in fall of 1967.

But BMW’s own factories were bursting at the seams for more capacity, and hardly anybody bought the Glas holdovers. By the fall of 1968 they were gone, pushed out to make BMW motorcycle components and, soon after, to make way for a massive factory expansion.

Hans Glas GmbH

The Glas company went far back beyond automobiles, to the mid-19th century when Bavarian farmer Johann Glas started repairing and building farm implements for his neighbors. Son Maurus Glas turned the enterprise into a proper business in 1860.

By the 1890s it was run by grandson Andreas, the company grew from 15 employees to 300 before moving to ever larger premises at Dingolfing in 1906, when Andreas partnered with a new investor for expansion and changed the company’s name from “Bavaria” to “Isaria.”

Born in 1890, Hans was one of Andreas’ 18 children. At 20, he moved to the United States to become a banker, but quickly lost everything he’d brought with him to poor investments – ending up destitute and working in an ice cream parlor, which also failed, leaving him sleeping under newspapers in a park.

Thanks to the kindness of strangers – a friendly doctor, in his case – Hans ended up getting jobs at Ford and Harley Davidson, where he gained valuable manufacturing experience. He returned to Germany in 1924 and took over for his father. By then it was part of a larger industrial concern, the Stumm Group, which fell into financial trouble during the depression. Hans was able to buy back the factory from the shareholders, but only narrowly.

The dual experiences of losing his shirt in Banking and almost losing the family business likely informed his later extreme aversion to debt and mergers, and his need to keep tight control over Glas’ books. He continued to lead the company through the war, when it was forced to produce munitions and his previously-university-bound son Andreas drafted, and emerged from the conflict in a good position. The “werke” was reorganized into Hans Glas GmbH in 1949.

Farm implements were needed in de-industrialized postwar Germany, but the boom in business didn’t last long and Isaria’s products archaic. Son Andreas, fresh out of a POW camp, invited a friend he’d been stationed with, engineer Karl Dompert, to come and help make the products, and the methods for making them better.

Until Dompert’s arrival, the Isaria corporation had a natural flow and had never ventured far from farm equipment. But farm tools were not enough to carry the company forward. Having seen how popular scooters were in Italy on a trip to Verona, Andreas and Dompert decided Glas should build one too.

The little scooter they created was named “Goggo,” tweaked from “Goggi,” a name given to Andreas’ baby son. It was a simple tube-frame bike with 150- or 200-cc two-stroke engines anda pretty optional sidecar. It was immediately popular, and the workforce at Dingolfing had to be expanded because demand was so high.

Scooters led directly to microcars – which were weatherproof – and Andreas and Dompert cooked up their own microcar starting in 1953. The goal was, as with the scooters, to build everything in-house, under just one roof. It would be small – with just 250-cc, but look like a proper car and have reasonable room for two adults and two kids.

The design, created personally by Andreas, Hans, and Dompert along with engine designer Felix Dozekal, emerged as the 1955 Goggomobil. Because they did it all in-house, except for the machine parts needed to stamp out the bodies, the Goggomobil cost only 100,000 Marks to develop, and had a sale price of less than 3,000 marks – much cheaper than a VW Beetle for a car that was genuinely cut above an Isetta or Messerschmitt.

The Glas Cars

The Goggomobil was just as successful as the Goggo had been – maybe more. In the first eight months more than 10,000 rolled out of the factory and by mid-1957 Hans was on the cover of Der Spiegel thanks to the huge popularity of the cars.

Exports reached as far as Australia and the United States, and employment at Dingolfing expanded again and again as Hans invested the profits from the early Goggomobil sales into creating more models, bigger engines, van and truck versions, and even a fancy hardtop. By 1958, 200 cars a day were leaving the factory.

Throughout this period, all of the management practices of a small 1940s farm-equipment company remained.

Hans did all of the accounting personally in a black ledger book. Everything expense related went through him, and he never borrowed if he could avoid it. He understood that, like the bubble in farm equipment after the war and scooters after that, microcars would eventually give way to customers wanting more. The next step was developing a proper car, and quickly before the boom ended.

The “Big Goggomobil” first appeared at Frankfurt in 1957 as a front-driver and went into production in the summer of 1958 as a rear-drive car, which was the first indication that development had been rather rushed. Although the “Big Goggomobil,” relabeled as the “Glas Isar” in 1959, was eventually tamed, the early days a steady stream of headaches. Engines deformed under heat, and the shell proved so flexible that windshields would periodically pop out until structural bracing was added to the shell.

Glas was inundated with warranty claims because of the Isar, and though the Goggomobil was still a strong seller, Hans would not take any outside investment. Nor was he a fan of Bavarian Minister of the interior Alfons Goppel’s 1959 plan to have Glas, BMW, and Audi merge into a single “Bavarian Car Works.” At the time, all of them were struggling and Goppel, who would soon be Bavaria’s prime minister, wanted to safeguard jobs.

Instead, Hans, Andreas, and Dompert doubled down on larger cars and created a series of new designs that they rolled out in quick succession in 1962 and 1963. The Goggomobil kept selling – providing at least some back stop for the financials for these new cars.

This time, Andreas and Dompert ironed out many of the kinks beforehand and added something new. They hired BMW engineer Leonhard Ischinger and had him lead the project. He also developed a new engine, a 992-cc overhead-cam four driven by a replaceable toothed belt. The free-revving cambelt engine was innovative and strong, though it was housed in a car that owed much of its origins to the Isar.

The Glas 1004 went into production in early 1962 and soon gained 1,189-cc (1204) and 1,290-cc (1304) versions. Styling was sixties square, but the car got good reviews. But Glas wasn’t done. To prove how good they could make a product and graduate to the big leagues, in the background the company had developed a midsize sedan and a sports car.

Enter: Frua

Glas’ staff was limited to the relatively small talent pool it had at Dingolfing, and though they were talented, there was on so much they could do on their own – and none of them were professional exterior designers or stylists.

To be able to take on the middle of the market or compete with sports cars from MG or Fiat, Hans, Andreas, and Dompert turned to Pietro Frua, whom Andreas met at the 40th Frankfurt IAA in early November of 1961. Glas must have been quite ready to roll after that initial meeting, because Andreas and Frua met again at the Turin show only three weeks later and a contract was signed on December 21st.

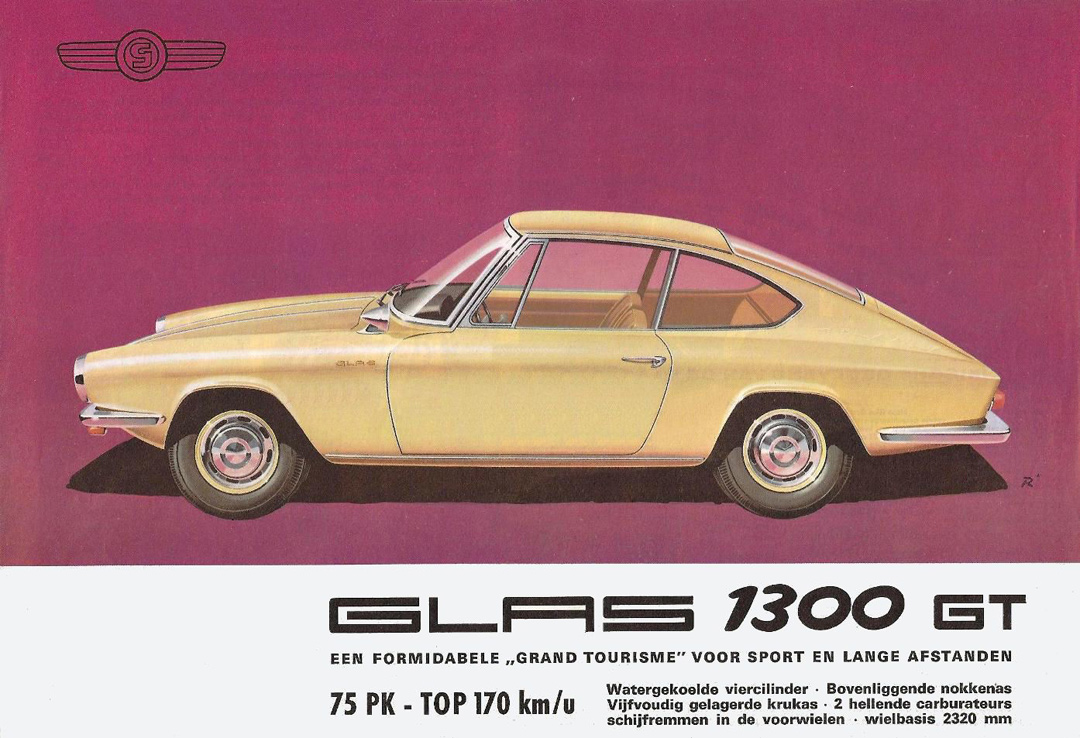

Frua would design two cars as a part of this contract, commissions 315 and 320/321. The first was for the Glas 1500 sedan, the second set was a sporty couple and a related convertible, which became the 1300 GT and larger-engined 1700 GT.

While the home team developed the mechanical pieces around Ischinger’s new engine family, Frua himself started on the styling in March of 1962.

Frua, by then a superstar stylist who was running his second coachbuilding shop after selling his first to Ghia and being a staffer at Ghia for some years. He was in a particularly fertile period. It was no surprise his Glas sedans ended up looking Maserati-like, he was penning the original Quattroporte (commission 317) at the same time. That same year he penned the Mistral (322) and Mistral Spider (325).

The coupe and convertible used some themes he’d already tried out on a set of Giannini Fiat 850s and the A-pillar and windscreen looked Mistral-esque, but the roofline and the details were new. They looked low-slung and sleek, and Glas and Dompert approved them almost without changes that fall. Glas was a good customer, and in the background he also had his staff build pickup and Mini Moke style versions of the Isar, both for possible production, though that didn’t happen.

Frua styled the car and the in-house team engineered it to use as many common parts as it could, but there was no way to make the bodies at Dingolfing, so that work was farmed out to Maggiora in Moncalieri, just south of Turin.

This, it proved, was a complex process. The floorpans and some other panels were made in Germany and shipped to Maggiora, who built some of the exterior panels and assembled the bodies. The finished bodies were then trucked to Dingolfing for final assembly. It was not a cheap car to build, and almost impossible to build in the kind of numbers Fiat or BMC did.

But it was a good sports car. It debuted at the 1963 Turin show in coupe and convertible form and immediately won fans. It was strictly a two-seater, but spacious inside for what was not a big car, and with good reflexes and fairly good power by the standards of the day – it made 85 horses from just 1,289-cc, good for over 100mph through four speeds.

Up front it had a double wishbone setup and out back a live axle on leaf springs, not so different from other conventional sports cars back then, but it performed in a much more sporting way than any previous Glas. Initial sales were decent, although it wasn’t a cheap car, and it was exported fairly widely – though never in any great volume.

Both Glas and Frua kept wanting to improve on it. In 1965, Glas added its much larger 1,682-cc four from the 1700 sedan to the car to create the 1700 GT, and in time it also got a five-speeder. Frua eventually tried his hand at creating a four-seater version, but it looked much bigger and more upright. The prototype kicked around until a Glas employee bought it, but it was eventually written off in an accident.

BMW Takes Over

In the background, the 1500 project did not work out so well. Glas showed the prototype at the 1963 Frankfurt show, but it wasn’t ready for production for another year, and when it did arrive, it had a bigger engine and different specs – hence, it became the Glas 1700. In the meantime, BMW had launched its Neue Klasse 1500 and 1800 sedans, which were extremely popular right out of the gate.

The 1700 emerged late and though Glas promised a version with an automatic, it didn’t show up until 1966. Production at Dingolfing was constrained and once the car was ready, Glas couldn’t actually build very many of them. The result was that Glas had spent a significant sum of cash on a car that it couldn’t build in any quantity, let alone compete with BMW or Opel.

Not to be put off by that reality, Glas continued to develop a V8 flagship, again with Frua’s help and based on pieces from the 1700. The V8 “Glaserati” eventually did arrive, but by then Glas was in deep financial trouble.

After the Isar debacle and the eventual slide in Goggomobil sales, outside partnerships had to be entertained. The first was Volkswagen, with whom Hans, Andreas, and Dompert met at various points in 1962-63, but VW wanted to close Dingolfing and use it as a development facility, which would mean massive layoffs – unacceptable to Hans.

Glas pressed ahead but the cash flow position of the company grew ever more precarious, and in October of 1965, Hans had to appeal to the Bavarian government for help.

A loan came through, but under the glare of inspection from state officials, it was clear that the methods of production at Glas were outdated and inefficient. They were alright for producing Goggomobils (which were still rolling off the line), but could never scale up to BMW or Opel-like volumes.

Also, too much of the business flowed directly through Hans, whose methods were similarly dated. He often refused to spend money on new tooling or new assembly practices because he didn’t want to borrow against the company, even if capital improvements were needed.

When the public learned of Glas’ ailing finances, sales began to slide, which made the situation even worse.

A second possible suitor was BMW, and here there was a personal connection. Andreas was friends with Georg “Schorsch” Meier, “The Cast Iron Man.” Meier was a legendary motorcycle racer who’d won many events for BMW and was synonymous with Munich’s motorcycle business. He was still a beloved figure within BMW though he had moved on from racing and into his own business (for a time, he was involved with the Veritas sports car).

Meier facilitated delicate, long-ongoing talks between the two automakers, which by the late summer of 1966 amounted to a BMW rescue of Glas. The deal was signed on September 27. Andreas and Dompert would remain, Hans would retire. Since Glas was in such dire straits, nobody was quite sure what BMW would do with its new purchase.

BMW 1600 GT

Most of what BMW got out of the deal was talent – Glas’ engineers had that aplenty, even if the cars they wanted to build were beyond the factory’s scale. Inventions like the toothed cambelt and the innovative hatchback wagon body on the 1204 found their way directly into future BMWs.

To everyone’s relief, BMW assured the staff that Dingolfing would not, in fact, close and that no jobs would be lost.

For a little while, production would continue as normal until the Glas models could be adapted into BMWs. The Glas GT and the V8 would become BMWs, the 1700 would continue on as a Glas. The changes to the V8 consisted of punching up the engine to 3 liters and putting BMW roundels on it, but the GT got more attention.

On December 8, BMW summoned Frua to Dingolfing for a long meeting about the GT and how it could be changed. Frua at the time was contemplating building and selling the car himself if BMW cancelled it, but that was not what happened.

BMW design boss Wilhelm Hofmeister (he of the “Hofmeister Kink”), development chief Bernhard Osswald, and BMW chassis man Alfred Böning sat down with Andreas Glas, Dompert, engine man Ischinger, and Frua for a long talk about how the GT could be made into a BMW and possibly made cheaper.

To keep the GT going as a BMW it would have several engineering improvements – starting with BMW’s 1,573-cc engine from the Neue Klasse. This boosted horsepower to 105 and gave the car even more speed. The shell was redesigned to mate up with BMW’s semi-trailing arm, coil spring rear, which made it a far better handler than before – and the original was no slouch.

Frua was tasked with altering the styling at as little cost as possible to add the traditional BMW Grill – Hofmeister suggested raiding the parts bin from the then-new 1600-2 to save time and money, and sure enough, its tail lights were added to the production car unchanged. It would have clear BMW branding up front with some small Glas branding in the rear. Production of the updated car commenced in September, 1967.

The convertible, which had been built in small numbers, did not officially continue, though one example was built.

By every measure, the 1600 GT was an excellent machine – coachbuilt, beautiful, and with a comfy cockpit that rivalled pretty much any contemporary sports car. BMW may not have been as enthusiastic about it as its home-grown products, but it didn’t compete with any other model, and while not “cheap” at 15,850 DM (about $4,000 at the time), it wasn’t expensive for something so exotic. Unlike the Glas versions, the BMW 1600 GT wasn’t exported to North America, but it was sold in other countries. The silver example seen here is said to have been sold new in Congo.

Despite all that, hardly anybody seemed to want to buy it. Despite a big spread at the Frankfurt show in September, by November only about 150 cars had been built. BMW 1600 GT sales to the cognoscenti continued at a slow pace through the spring. In March, Frua visited Munich only to be told that the car would be cancelled on August 30th.

After Glas

All of the Glas cars that weren’t the Goggomobil were relatively low volume, and it was Glas’ poor economy of scale that got it into trouble in the first place. BMW was not really interested in the 1700, since it competed directly with a BMW product and was a pain to build. At the end of 1967, the line was shut down and the tooling was sent to South Africa.

The 1700 wasn’t so different from a BMW product in some ways, and the lower volume operation in South Africa got a unique model out of it – lightly restyling the front and rear to look more BMW-like and building the cars locally into 1974.

The “Glaserati” V8 was an extremely niche product, and only a few hundred of each iteration (the original 2,580-cc version and the later 2,982-cc version) were made before BMW decided to end production in May of 1968.

The BMW 1600 GT then ended up the last Glas car still in production at Dingolfing, if only for a few months and as a lame duck. When the bodies were used up (and a few of the original order may never have been finished), so was the car.

There was plenty of room to expand around the site, and BMW went that route – opting to build a much larger Dingolfing complex starting in 1970 – the site of manufacture for the first 5-series three years later. Dompert was the person chosen to lead that project, and he remained head of the Dingolfing factory until 1983.

In the in-between period, after the GT was gone but before factory construction began, the Goggomobil was allowed to run out the clock still in production – the last one was built on June 25, 1969. BMW motorcycle parts were also built there and at Glas’ much smaller parts facility in Landshut.

The family lost the company but got 10M DM in return. Andreas Glas later said he was grateful that the factory had survived at all, and praised BMW’s efforts at expansion even if they came at the expense of the Glas cars.

Just 1,255 1600 GTs were made, and they’re probably the most obscure BMW of the 1960s thanks to those tiny numbers. It’s estimated only about 100-200 still survive – numbers not helped by the tendency of the bodies to rust. This one, built in late 1967, was privately imported to the USA in 2018 and is owned by collector Norm Walters.