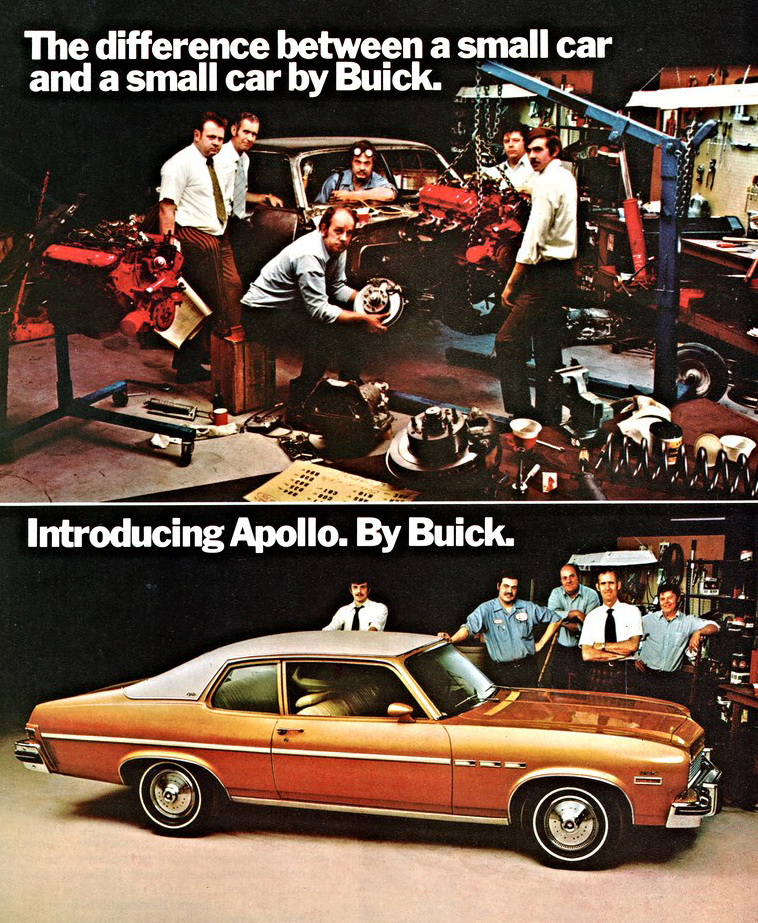

You’d think that a “smaller” car launched just before a fuel crisis would be almost a sure fire hit, but not so with the Buick Apollo. It might have been smaller but it wasn’t “small,” and the very things that Buick used to differentiate it from its humbler siblings worked against it after OPEC.

The Apollo, new in 1973, was offered for just 28 turbulent months, the last twelve of them with a reduced lineup.

Ever since it first appeared, the car’s been perpetually caught in the middle of the rapidly changing circumstances around it, its siblings within GM, and different eras. It was introduced late for the 1973 model year on April 12 of that year, and it was intended as a return to the “compact” market.

A Return to Compacts

As the A-body Skylark/Special had grown larger in the 1960s, Buick (and Olds and Pontiac) had gradually abandoned actual compact dimensions – in 1973, the former “compact” A-bodies were now quite large “intermediates.”

Indeed, some owners of aging 1960s Skylarks did trade them in on Apollos after waiting for a similarly-sized replacement (or at least so they told Popular Mechanics at the time). But the goal for the Apollo was to shore up the bottom end of the lineup as strong interest in compact domestics returned, like the Ford Maverick/Mercury Comet.

Buick had the Opel line (albeit with a limited set of models) for import fighting, but kept asking for a smaller domestic car for customers who weren’t interested in the German cars. Olds dealers, who didn’t even have Opels, clamored even louder.

GM answered their requests by applying the “Ventura” treatment for two new Buick and Olds models. In 1971, it had created a variation of Chevrolet’s popular X-body Nova for Pontiac to sell – the Ventura. Now Buick and Olds got their own – Apollo and Omega – for a clever acronym – the N-O-V-A cars.

As with the Ventura, each was given unique styling elements out front and a unique rear fascia, with the Buick even getting the traditional “ventiports.”

Though all these cars were theoretically aimed at “economy” customers, they weren’t really “economy” cars. They were much larger than most imported cars and Chevrolet had slotted the Vega beneath the Nova starting in the summer of 1970. Post OPEC, Vega variations would also come to Buick, Olds, and Pontiac, but that was still in the future.

Apollo and the Nova Cars

All of the NOVA cars came with a base Chevy 250-cid six, but each were offered with divisional V8s. At the time, you could get 350s V8 from all four divisions, but each was unique. The rationalization of engines that led to the infamous “Chevymobile” incident (in 1977) or the consolidation of powerplants (in the 1980s) had yet to happen.

The Apollo was marketed as a smallish semi-luxury car despite the interior’s clear origins in the much cheaper Nova. The 2-barrel and 4-barrel 350s were emphasized in the marketing. This was, after all, a Buick and had a proper Buick powerplant. The 4-bbl 350 combined with the good handling of the Nova and optional front power disc brakes made the top-spec Apollos a rather quick car with handling drivers liked.

They came as a four- or two-door sedan, or a handy 2-door hatch – a body style that was added to the Nova in 1973 and shared with its sisters. About 20% of Apollos were hatchbacks, a pretty good percentage for a new idea for Americans.

The extra-large hatch made for huge amounts of easily-accessible luggage space, but lots of drivers complained about poor sealing and lots of wind noise. In fairness, the NOVA cars’ hatch was much larger than most other hatch panels on European and Japanese cars at the time.

Still, the car got generally good reviews even if there was an obvious acknowledgement that it was a rebadged Nova.

At the top of the line was an Apollo GSX in the mold of earlier Buick Skylark GSXs, although this package was only offered in the 1974 model year. As at Pontiac, where the mighty GTO was made into an option for the Ventura in 1974, the GSX was more show than go. Compared to previous GSXs, it was also visually restrained – mostly badges and side trim.

Then came OPEC. The Apollo might be smaller than the other Buicks but the Buick 350 – particularly with the 4-bbl, was not an economy motor. Its 14-15 mpg thirst did nothing for it in terms of marketing to suddenly fuel-conscious buyers, even if it looked like a Volkswagen compared to an Electra 225.

Curiously, the Nova and Omega V8s were observed to be about 2-4 mpg better at the time, not that they were so frugal either. A nearly 140-day supply of Apollos stacked up by mid-1974. The car wasn’t a terrible seller overall, but never did as well as Buick dealers would have liked.

In 1975, all the Novas were totally restyled and the Skylark name returned at Buick, supplanting the Apollo coupes. At the end of the year, the Apollo’s brief story came to an end when the remaining Apollo sedan was relabeled a Skylark for 1976.

Epilogue

The Apollo cost more than a Nova when it was new, but as an old car it’s often a cheaper buy in 2-door form, because collector and hot rod interest in Novas is very high and the Apollo isn’t a Nova even it’s really close.

Unlike later Buick versions of the Nova and Monza, the early Apollo had a real Buick V8, which sets it apart mechanically from the Nova as well – if you want performance parts, they need to be for the Buick 350. In 1975, the Apollo Sedan saw the beginning of rationalization, with an Olds 260 as an option.

One bright yellow 1974 Apollo played a key role in the future of Buick that year when GM engineer Cliff Studaker pulled an old early 1960s Buick “fireball” V6 from a junkyard and dropped it into said Apollo. The idea was to demonstrate the V6’s continuing viability to GM’s Ed Cole.

The drive Cole took in this test mule led to GM buying back the engine from then-owner AMC (who had mothballed the tooling and were no longer using it). Reunited with Buick, the V6 (reworked into the “even fire” V6 in 1977) would go on to power many of the Apollo’s successors.

This Apollo was seen at the amazing Browne Auto Salvage.