It would ultimately prove a highly influential, pioneering car, but the Chrysler Airflow was infamously too much, too soon. Its streamlined shape, honed in a wind tunnel and not just a designer’s imagination, spawned imitators as diverse as the Peugeot 402, the Toyota AA, and the Divco Milk Truck, and it was comfortable, safe, and very fast by the standards of 1934. Those futuristic looks were, unfortunately, its undoing. Just too weird for Americans, only about 30,000 were sold in four years before Chrysler threw in the towel in 1937.

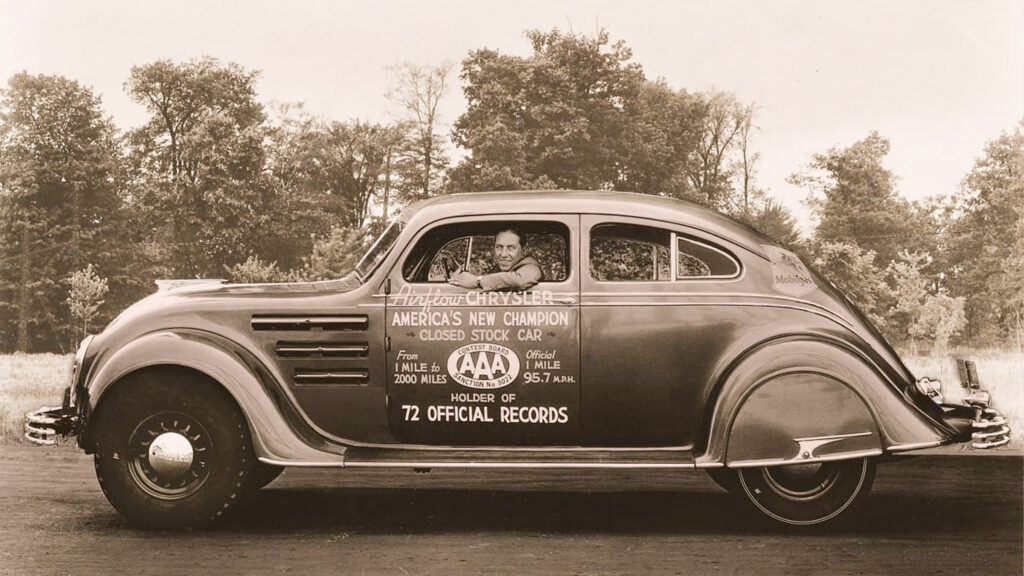

Stung by consumers’ rejection of this highly ambitious car, Chrysler shied away from taking stylistic chances until the fabulously finned “Forward Look” cars arrived 20 years later. But over time, the Airflow’s influence on later cars and its high-tech reputation even redeemed it to the company’s marketers. In 1964, the then 30-year-old Airflow was featured in a Chrysler ad that touted not only its style but also its semi-unibody construction and 72 stock car speed records, though the ad copy did lament that the car had been ahead of its time.

Last year the Airflow turned 90 and, though you’d never have know it by the lack of fanfare (and lack of a collector’s edition Pacifica), the Chrysler brand turned 100. (The actual Corporation, founded a year later, celebrated in 2025.) The Airflow is the last great car of the era when Walter P. Chrysler was still involved in the company’s day-to-day operations. To take a look back at the car and the company’s early glory days, I tracked down the unrestored 1935 Chrysler Airflow you see here and learned more about what its like to live with from owner Les Willman.

Being a ‘35, this one has the less controversial front end look that Chrysler hurriedly grafted on when initial sales disappointed. But while the Airflow’s styling gets much of the credit (and blame) for its fortunes, the car was just as radical underneath as it was to look at, and it probably wouldn’t have gotten built if its primary purpose had been aesthetic.

Airplanes, Wind Tunnels, and Chrysler’s Glory Days

The 1934 Airflow debuted at New York’s Grand Central Palace almost ten years to the day after the original Chrysler Six. By then, the Depression had bitten the company hard, but it wasn’t hubris to launch such a radical car.

In those ten years, Walter P. Chrysler and his “Three Musketeers” of engineering, Carl Breer, Fred Zeder, and Owen Skelton, had built an automotive powerhouse from the dying firms of Maxwell and Chalmers. In 1928, they launched Plymouth and DeSoto, and the Corporation bought Dodge that same year. By 1931, Walter P. would be a two-time Time magazine Man of the Year, looking out on the world from the Cloud Club atop his eponymous New York Skyscraper, briefly the tallest building in the world.

The Musketeers made the product happen, and they went back even further. Breer, a graduate of Throop Polytechnic (now CalTech) had met Zeder at Allis-Chalmers in 1909. Both then moved to South Bend, where Zeder hired Skelton, formerly of Pope, Packard, and Benham, in 1916. Chrysler recruited the trio to Willys-Overland in 1920, only to find himself ousted there before he could put them to good use. Still, by 1927, their engineering decisions had created a legion of popular, high-quality cars that built Walter P.’s empire.

That summer, on a drive to Port Huron, Michigan, for a family weekend at the beach, Breer spied a bunch of military biplanes flying slow and low en route to nearby Selfridge Field. He marveled at how they could stay aloft at such low speeds, then stuck his hand out his car window and angled it like a wing. As air flowed over his hand, he wondered why lift, drag, and downforce, so well understood in aviation, were all but ignored by car engineers.

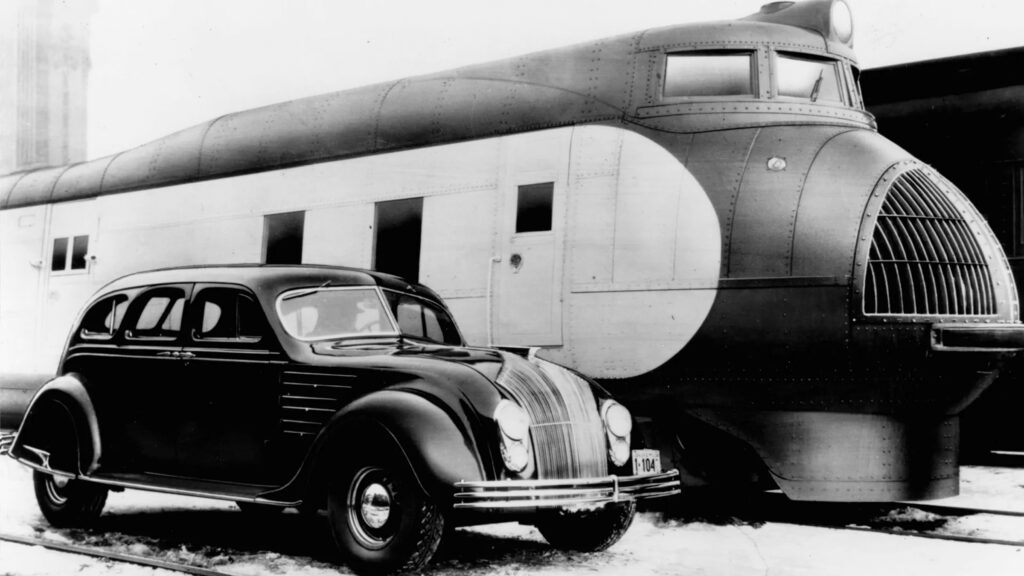

After his weekend revelation, Breer set about tiptoeing into aerodynamic car research with the help of a friend, Ohio engineering consultant Bill Earnshaw. A friend of the Wright Brothers, Earnshaw (supposedly with Orville Wright’s assistance) helped Chrysler set up a small-scale wind tunnel. Breer quickly found that teardrop shapes were the slipperiest forms and that 1920s cars were, in aerodynamic terms, worse than barn doors.

Their carriage-like bodies were often 30% more aerodynamic in reverse than they were going forward, resulting from having a long hood and a cabin pushed all the way back in the chassis to make room for a solid front axle and a lengthy front-mid engine setup. To get closer to a teardrop, the engine and cabin had to move forward, which led Breer and body designer Oliver Clarke to start sketching out new packaging ideas. This is where the Airflow was really born.

All of the Airflow’s Firsts

Moving the cabin forward put the rear passengers ahead of the rear axle while moving the engine atop the front axle made the hood much shorter. These two changes alone yeilded a much larger cabin and a vastly smoother ride. Softer spring rates, enabled by the new weight distribution, reduced the jounce frequency, making the ride feel even smoother. In the 1930s, when most leaf-sprung, solid-axle cars rode like unladen old pickups and “ergonomics” was a word few people had ever heard, these were genuine innovations—probably the real reasons the Airflow reached production.

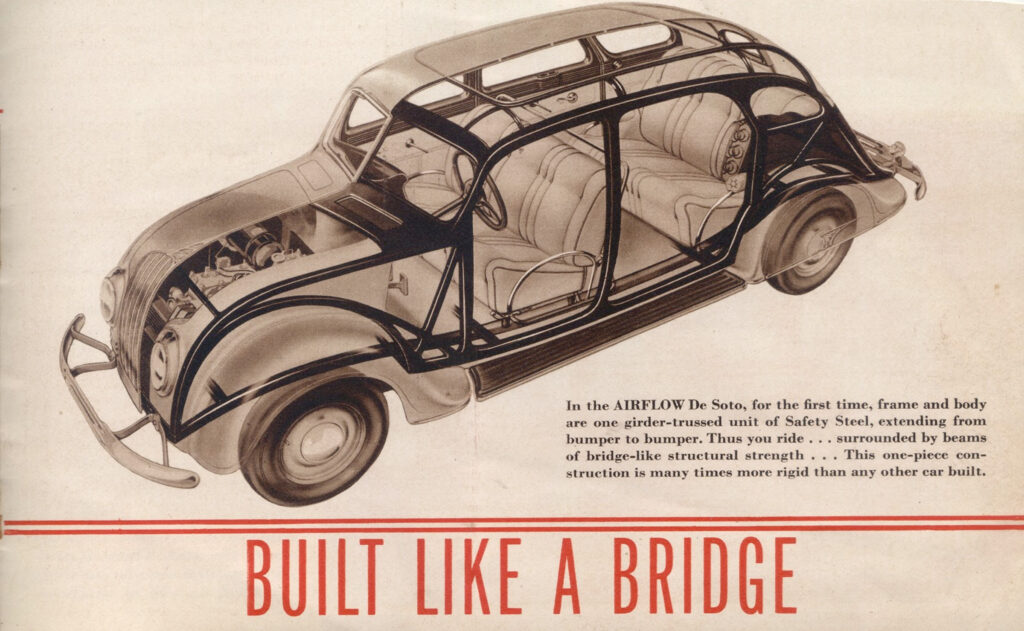

The structure needed to do all this was complex, so Breer decided the car should have a unibody and all-steel body panels, no wood framing. Some of Chrysler’s bodies were already all-steel (though canvas top inserts remained, as steel stamping technology was still evolving), and this wasn’t the first unibody car (hello, Lancia Lambda), but the steel skeleton was a first for the American auto industry.

The Airflow wasn’t quite a full unibody. It used what Chrysler called a “bridge and truss” design, which used a spaceframe with exterior panels welded to form a strong structure. Once everything was welded, Chrysler PR said, the structure was 40 times stiffer than a body-on frame design and about 200 pounds lighter than an equivalent body-on-frame Chrysler. To demonstrate its toughness, Chrysler pushed an early Airflow off a 110-foot cliff with cameras rolling, then drove it away.

This new structure also had other advantages. The stronger body meant you could move the A-pillars out wider, blocking less of the driver’s vision, and Chrysler worked with PPG to develop a curved one-piece windshield for the car, though it was so expensive that only the top Airflow Imperials got it. That meant designing new windshield wipers that would work on curved glass, another first. The body structure allowed for better cabin ventilation and for access to a meaningful trunk area behind the rear seats.

There were other firsts too, like tubular seat mounts and structures, the latched, front-opening “alligator” hood, an optional Borg-Warner electric overdrive, a powered divider in the CW-Series Imperial Airflow limo, and the under-glass flush headlights of the ‘34 DeSoto Airflow. And, of course, the aerodynamics meant a top speed of over 95 mph on the eight-cylinder models and, Chrysler claimed, up to or even just beyond 20 mpg. The engines, all flathead straight sixes and eights, were carried over from earlier cars and were as dependable as death and taxes.

Hushed and Rushed

Amazingly, Airflow development continued through the depths of the Depression. The economic outlook made the cost and complexity of the car even more of a risk but also more of an opportunity. A working prototype, named “Trifon” (supposedly in honor of test driver Demtrion Trifon), hit the road in September 1932. Thousands of hours of testing and refinement occurred that fall at the nadir of the economic crisis.

Since testing the cars in Detroit would instantly give away how radical Chrysler’s new car was, the Breer and the Musketeers arranged to test it in Northern Michigan, on deserted farm roads and a vast rented estate near Grayling. When the cars had to go back to HQ or near population centers, they went into covered trucks. Locals did see the cars on the road, and in his later memoir, The Birth of Chrysler Corporation, he wondered how surprised they must have been by these land-borne UFOs blasing past their aging 1920s touring cars and farm trucks.

Interestingly, the styling came together after the structure—Chrysler was an engineering-led firm. Despite the pretty art deco looks of the car, it really was “fashioned by function,” just as the ad copy would soon say. The early prototypes were slightly different shapes as Clarke and his deputies worked to differentiate and finish the production versions.

There would be two variations. Chrysler would sell eight-cylinder Airflows and Imperials but keep its conventional six-cylinder cars while DeSoto would replace its entire lineup with six-cylinder Airflows. Production was to commence in 1934, but with so many things to engineer and finalize, there was zero chance of a fall 1933 introduction. Instead, Walter P. and the marketing team wanted to introduce it at the January 1934 New York Auto Show. It was here where things began to go awry.

The Airflow was the undisputed star of the New York show, and Chrysler took thousands of orders, but it had no cars to deliver until late April. In the intervening months, rumors ran rampant that the cars were not in showrooms yet because they were too advanced and full of potential quality ills, Breer would later relate. “To me, it was not so much that the airflow was ahead of its time as that Airflow production was way behind time.” Many orders evaporated, and even once the cars arrived, they didn’t sell.

Having nothing else to sell, DeSoto dealers took the worst hit, and even though the Depression had eased a little, its sales were down 22% from 1933, while rival Oldsmobile saw a 28% rise. The car had a great deal going for it—it was fast and smooth, and it saved fuel—and Chrysler and its dealer body went on a huge PR blitz full of consumer testimonials, but nothing budged the needle.

Part of the problem was price. The car was a minimum of $120 pricier than what Chrysler DeSoto dealers had been selling in 1933. Most consumers were pinching pennies or on relief, and that sum could’ve bought you a bargain used car at that time, let alone the $995 starting price of the DeSoto Airflow. But then there was also the hood. In an era when straight eight engines and big hoods symbolized prestige, the Airflow’s design inherently prevented such a feature. The DeSoto’s hood was the shortest of all and almost impossible to fix.

For 1935, Chrysler tried grafting on a bigger hood, designed by Norman Bel Geddes and Ray Deitrich, while supplementing both the Chrysler and DeSoto lines with more conventional “Airstream” models created by body supplier Briggs. Sales continued to fall, and by 1937, only one model was left, the Chrysler C-17, with an even more prominent schnoz stuck on the front. Production ended that summer.

All The Airflows, And All The Imitators

In four years, Chrysler produced 29,832 “Airflow Chryslers” and 25,737 more DeSoto Airflows, the latter discontinued at the end of 1936.

Originally, there were four Chrysler wheelbases: the Airflow (118 inches), the Imperial Airflow (128 inches), and two Custom Imperial Airflows (137.5 and 146 inches, both with custom body options). All were straight-eight powered, from 299 cubic inches and 122 horsepower to 385 cubes and 150 horsepower in the vast CW-Series limo. All DeSoto Airflows came on a 116-inch wheelbase and used a 100-horse 242-cid straight six. The standard Chrysler and DeSoto models also came as coupes.

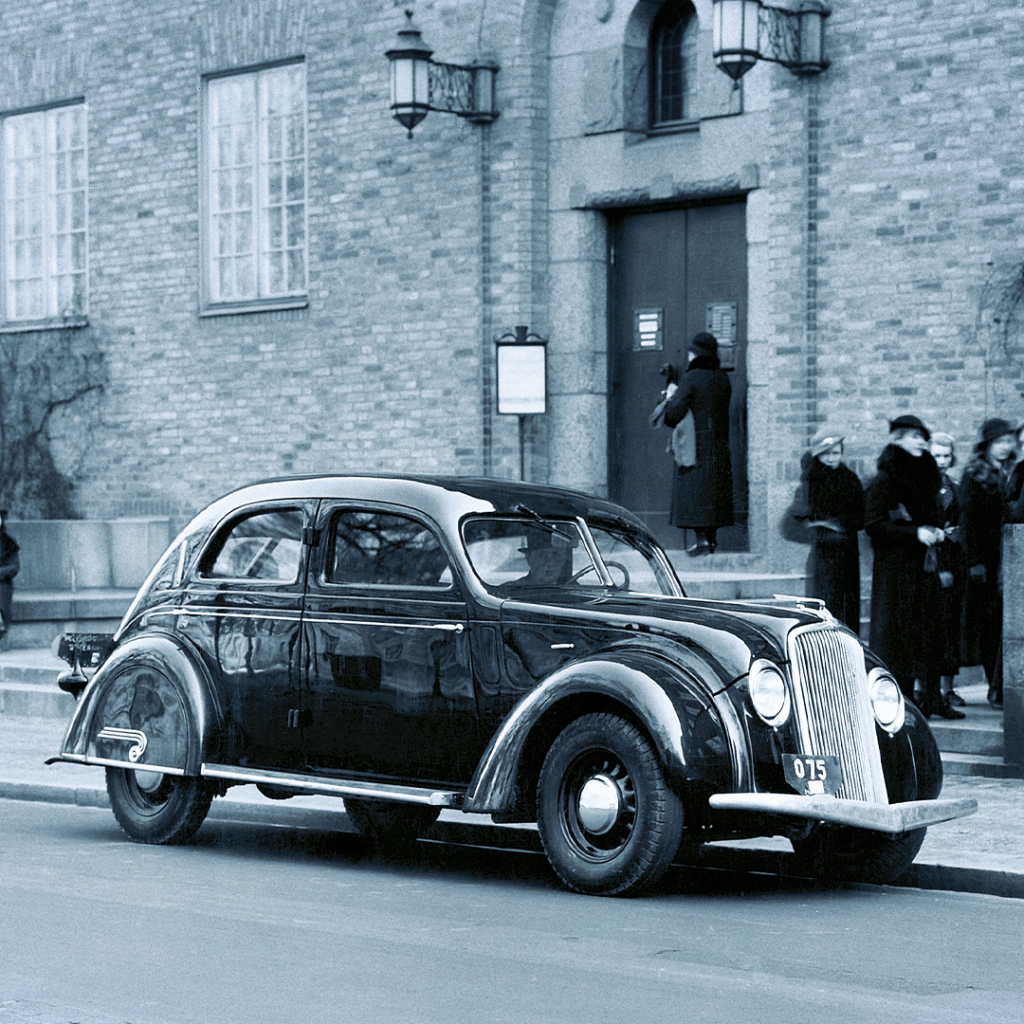

The cars didn’t sell, though many of their innovations were adopted by other automakers, like the one-piece curved windshield, and it gained many fans (and one notable hater) outside the US. In France, Peugeot crafted an entire lineup of cars (202, 302, and 402) that were sleeker than the Airflow but directly inspired by it. In Sweden, the Volvo PV36 even copied the grafted-on nose. In Germany, 1938’s Opel Admiral had clear Airflow influences, as did Toyota’s first car, the 1936 AA.

One person who wasn’t so pleased? Hungarian aerodynamicist Paul Jaray. Breer may or may not have known about them, but Austrian engineer Edmund Rumpler had built aerodynamic cars, and Jaray had shaped them in wind tunnels by 1927. After the Airflow’s debut, Jaray sued Chrysler for what he saw as infringement on his designs for Tatra, though Tatra and Chrysler were hardly direct competitors.

Driving and Owning a Chrysler Airflow Today

Les Willman is a Mopar guy, and his ‘35 Airflow shares the garage with a minty 1971 Dodge Challenger. But after years of fifties cars and muscle machines, he and his wife wanted a pre-war car. “We were watching a Barrett-Jackson auction a few years ago and a gorgeous 1930s Cadillac came across the stage. It was too expensive for us, but right behind it was an Airflow, and honestly, it was very reasonable.”

Indeed, the Airflow’s rep as an ugly duckly has kept prices low over time, and you can buy quite nice 1935 or later Airflows for less than $30,000. The earliest ones, coupes, and big Imperial versions cost more, but it’s very rare for all but the very best or rarest ones to crest into six figures. There’s also an Airflow club, which is helpful for parts sourcing.

Willman did not buy the Barrett-Jackson car but found this ‘35 in California for $25,000. “It did need more mechanical work than we expected; the brakes were bad, the tie rods were real sloppy, and somebody had started a 12-volt conversion but not finished it, so none of the lights worked.” With those things long completed, it’s a pleasant and reliable driver. “The paint buffed out nicely, and we had the dash repainted. All that wood that you see in the car is painted metal!”

“It’s very smooth, and when you get above 35 mph, it automatically shifts into the electronic overdrive.” Willman doesn’t take it on the highway much sees how it would’ve made an excellent long-distance cruiser in its day. At 90 years old, he doesn’t perhaps push the car as hard as one might in a typical HotCars write-up, but he does use it. It draws lots of questions. “People want to know what it is, and many assume it’s a European car before they find out it’s a Chrysler. I’ve even had people tell me about the Toyoda AA!”

Breer never gave up on believing in the car, and he was delighted when publications like the Autocar and books about the nascent collectible car world started giving the Airflow its due as a style and tech influencer. No doubt he’d be proud of Willman’s care for the car and his interest in it, even if things didn’t work out as planned.

Editor’s note: This story was originally written for HotCars.com, and first appeared on that site in 2024.