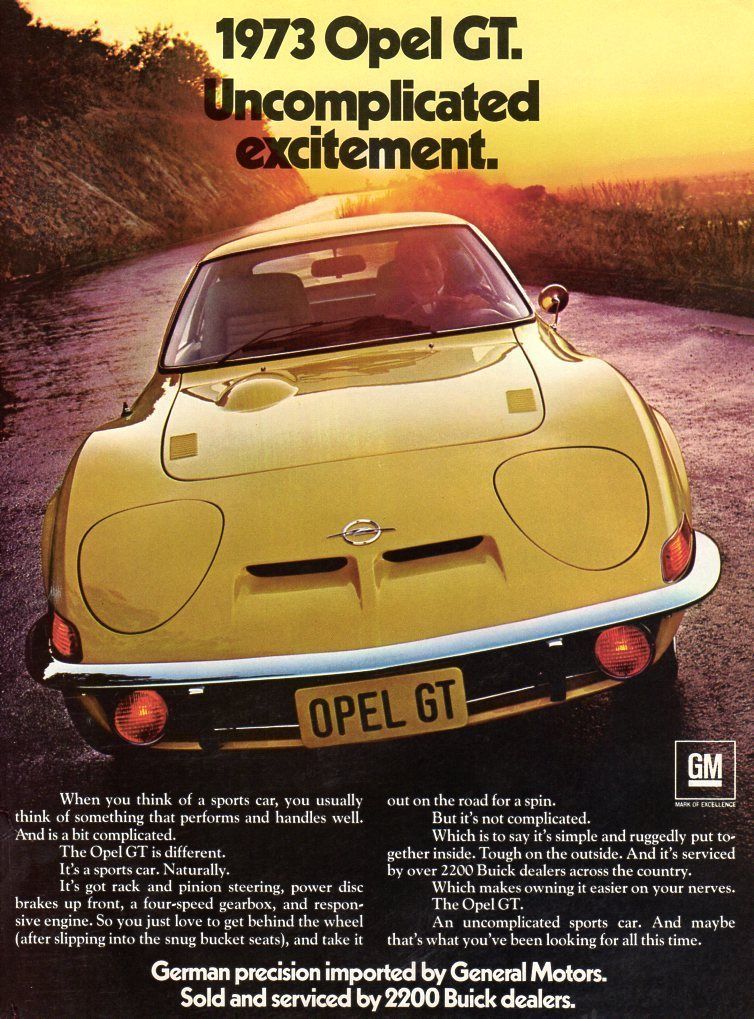

It must have been an incongruous sight for most Buick customers: a miniaturized German Corvette sitting in a showroom across from herds of loaded Buick land yachts. But the Opel GT was a big success both for GM’s German brand and for American “Buick-Opel” dealers. Despite never having sold anything like it previously, more than 100,000 of these little sports cars were made and 70% of them came stateside. Unfortunately even those numbers weren’t enough for a second generation, but it’s still a sought-after car today.

The cars in the background of the photo above set the date, probably the spring of 1980 judging by the X-car Skylarks and downsized Century sedans. By that time German Opel imports had ended, largely thanks to unfriendly exchange rates, and when (or if) GT customers returned to the store for a trade-in, they either had to go with a Buick (or maybe an Buick Opel Isuzu) or move on to another brand. Thus ended what was largely a very positive experience for both GM divisions.

Neither Buick nor Opel were associated with sports cars when the GT was being planned, and it wasn’t until long after the GT was gone that either brand tried such a vehicle again (at Buick, the 1988 Reatta, at Opel the 2000 Speedster). But the team who created the little car knew sports cars and U.S. showrooms quite well, and in the 1960s the times were a’ changin’. Buick’s relationship with Opel, however, started even earlier.

Buick and Opel

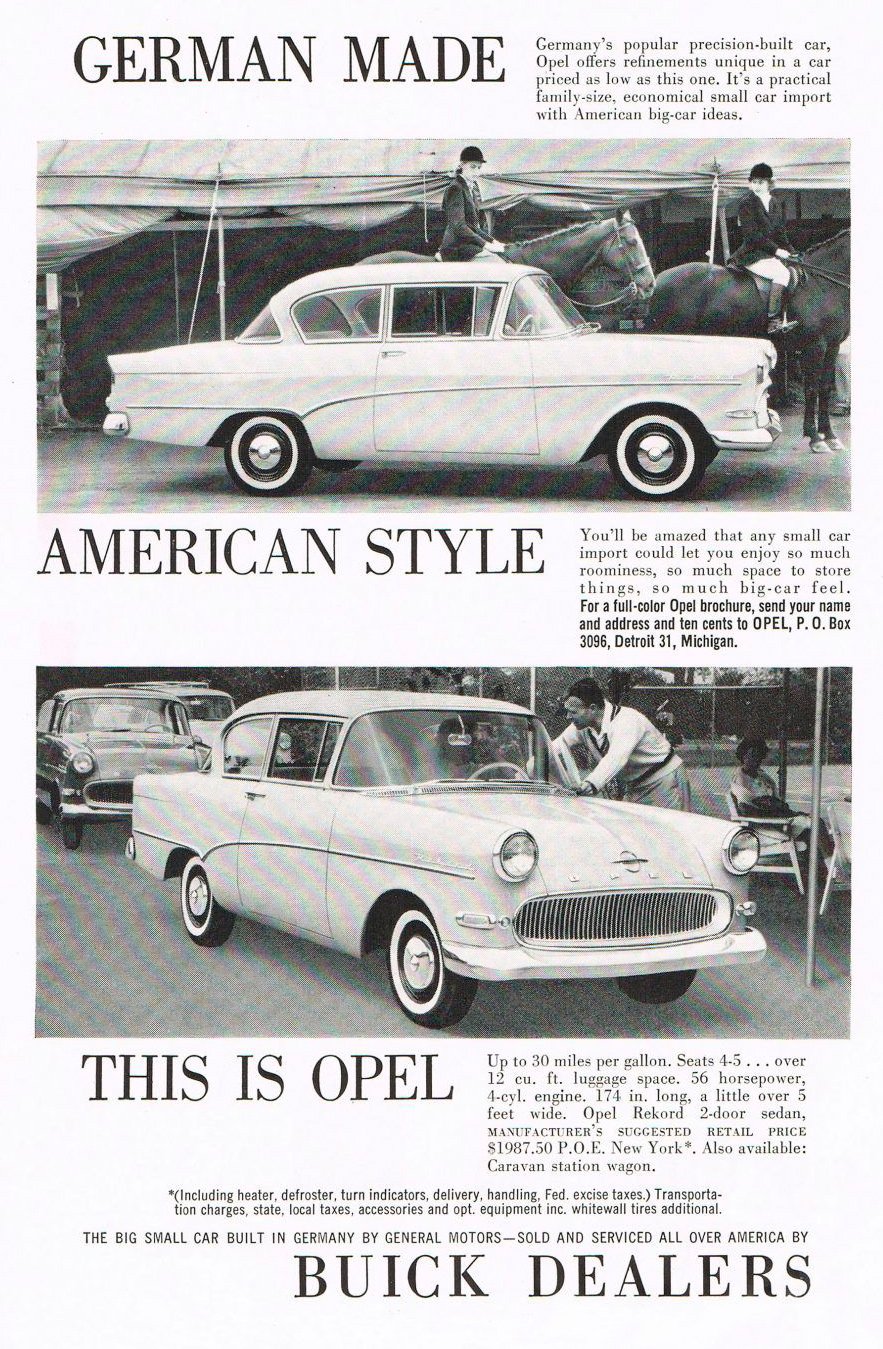

Flint’s finest had begun offering Opel Rekords as a successful sideline starting in 1956, a time when GM and the other big Detroit companies were just beginning to notice the steadily increasing numbers of imported Volkswagens and Renaults. The Rekord, larger than Volkswagens and Hillman Minxes and heavily influenced by Buick’s own products, was a natural fit until the 1960 Detroit “compacts” came along and wiped it off the map. Buick’s Y-body Special replaced it entirely in 1961.

But Buick didn’t give up entirely on having this sideline of small cars. In January 1964, it reintroduced Opels, but this time using the smallest model in the German automaker’s lineup, the Kadett A.

Reusing an old Opel name in a new format, the Kadett A looked very much like a scaled-down Chevy II. It modestly regained ground for “Buick Opels,” as customers sometimes referred to them, and sold in ever-larger numbers during the 1960s as Detroit’s “compacts” grew progressively larger.

The Kadett A’s resemblance to the Chevy II was not coincidental. Detroit’s design priorities had a heavy influence on both Opel and Vauxhall products in the 1960s, an influence that grew even stronger shortly after the German debut of the Kadett A in late 1961.

Early the following year, at the request of Opel’s Managing Director Nelson Stork, GM sent Chevrolet designer Clare MacKichan—who led many iconic 1950s Chevy designs including the famous Tri-Fives—to Germany to help build up a proper Russelsheim design studio and jazz up Opel’s conservative products. According to some reports, at the time Opel only had about a dozen draftsmen.

Clare MacKichan Goes to Germany

As instructed, in Germany “Mac” built up an expanded design studio and an experimental group led by Opel veteran Erhard Schnell.

MacKichan likely brought with him some of the shapes of two proposed Corvair-based sports cars, the Monza GT (XP-777) and Monza SS (XP-797). Both concept cars which were being worked on for a 1963 release, and they were slinky indeed, with “shark nosed” styling largely done by Larry Shinoda and Tony Lapine.

MacKichan had Schnell begin work on Opel’s very first sports car, then “Projekt 1484” in secret using themes from these two cars. 1484 was strictly a back-room project and Opel’s management had little interest in sports cars, but it gradually took shape in 1963 and 1964. By then Lapine had been transferred to Germany as well, although the primary designers of the GT were Schnell and Wolfgang Möbius.

A big secret, even Stork himself did not learn of the project’s existence for many months. Even after that, aside from young marketing exec Bob Lutz, the idea didn’t get much support for production until Semon “Bunkie” Knudsen became GM’s Overseas VP in 1965.

Knudsen knew and liked sports cars and allowed the prototype to be shown at Frankfurt that year, generating huge interest from the public. A reaction so strong, in fact, that management decided to build the car. Knudsen also understood that while conventional imported cars faced plenty of competition in America from Domestic cars, there really weren’t any domestic small sports cars, and that MGs, Triumph and Fiat sold huge numbers of them.

The proposed sports car would be built, but for cost reasons it had to be based on existing mechanical pieces. As MacKichan returned to the U.S. for a promotion, Schnell worked with his replacement—Chuck Jordan—to rework the car around the mechanical pieces of the then-new Opel Kadett B.

Building the Opel GT

Despite the huge popularity of the car at the Frankfurt show in 1965, it took three more years for the vehicle to actually get into production, and there were lots of small changes in the process.

A niche product from the outset, it was a battle to build the car the way the stylists wanted. While instructed to use as many Kadett bits as they could, the ultra-low hood and beltline meant relocating the engine rearward by nearly 16 inches and altering the chassis quite a bit, which added cost.

Designer-turned-technical director Hans Mersheimer supported this idea, and to demonstrate it to the board, he had prototypes built to the designers’ proposals and tested by former Porsche test driver Hans Hermann. Hermann’s opinion was that the altered cars handled much better, and given the public’s interest in the design that was all Opel’s directors needed.

But moving things around to fit them within the curvaceous design also meant some weird compromises and locating things in strange areas. The GT isn’t the easiest car to service. The rotate-around (not actually pop-up) headlights were manually actuated by a lever near the shifter, and even with the engine moved backward the hood was so low it required a bulge to clear the air cleaner. There was no trunk or hatchback—the shell was complicated enough to build as it was.

Opel projected a volume of 20,000 cars per year for global sale, which seems like a big number but wasn’t enough to justify setting aside a big part of a factory already making Kadetts or Rekords. The solution was outside contractors, and Russelsheim turned to French coachbuilders Chausson, to assemble the complicated shell, and Brissonneau & Lotz, then building Renault Caravelles, to paint, trim and finish them before the cars returned to Germany for final assembly.

There would be two engines offered, a wheezy overhead-valve 1.1-liter and Opel’s punchier cam-in-head 1.9-liter, both fours. A three-speed automatic would be offered, but most cars were sold with a four-speeder. There were also options like sway bars and a limited-slip differential, but they weren’t offered in the U.S.

The GT Arrives

After years of development, the first hand-build cars rolled into showrooms in the fall of 1968. The GT looked much like the brand-new C3 Corvette, no doubt a partial result of all the cross-pollination of studios (MacKichan returned to the U.S. in 1967 an was succeeded at Opel by Chuck Jordan) and certainly an advantage in helping sell cars.

The 1.1 offered style, but not power, and was not offered outside of Europe. Even the car’s sexy looks couldn’t convince more than about 3,500 Europeans to take one and it was quickly dropped, but the 1.9 was a different story.

Fast, quiet, stylish and reliable, the bigger-engine GT was an instant hit both in Europe and (especially) in the United States. The car got mixed reviews from the American press, some likening to a miniature Corvette in both style and handling, others not being particularly convinced of the latter because of its tiny tires and the lack of the sway bars Europeans could get. The styling was also an opinion splitter, but customers didn’t really seem to care what the critics thought. Nor did it matter that it was a little more expensive than a Ford Capri or Triumph TR6.

It did not hurt that the GT was also faster than several aging traditional cheap sports cars (like the MGB) and, being a coupe, a little more practical year-round, the lack of a trunk notwithstanding.

For the first 18 months or so, GTs flew off dealer lots until the 240Z arrived and began to bite into sales. Buick dealers were also selling lots of Kadetts at the time, and in 1970 Opel’s U.S. sales topped 86,000 cars, 21,000 of them GTs.

In total, 103,465 GTs were made, with 70% of them heading stateside, before Opel began to lose interest in the car in 1972-73. American buyers had also cooled on it, in part because the cheaper Manta A, which came stateside for 1971, offered similar performance and much more practicality. The market was gradually turning away from sports cars in favor of small coupes, and the Manta was well-placed to compete with the Toyota Celica and Mercury (nee Ford) Capri.

The End

As the GT aged, exchange rates began to bite into the profitability of Opel imports and a total redesign of the niche sports car was deemed too costly (and with U.S. impact bumper legislation looming, it surely would have been). Why bother when the market wanted Mantas?

Opel’s contract with Brissonneau & Lotz was also ending, and when it did so did the GT. Even late in the game, however, they still moved quickly at the Buick dealer. Nearly 12,000 U.S.-model GTs were sold in the final season of 1973.

The GT was not replaced in Europe, with many returning customers opting for Manta Bs instead during the Coupe-happy 1970s, but the Manta B was not offered in North America. Indeed, all German Opel imports ceased in 1975 thanks to the increasing costs of selling them in the U.S. The Buick-Opel idea continued with the Buick Opel Isuzu, but an actual Opel did not return to U.S. showrooms until 2008, when Saturn began importing the Astra.