It lasted just 14 seasons, but the Essex was one of the most successful cars of its era; and era which just happened to be a huge boom in car production and a cutthroat war between hundreds of manufacturers for market dominance.

The Hudson Motor Car Company created the Essex as a lower-priced companion to its upper-middle-class cars for 1919, and in that first year they built 20,000 of them. A decade later that number had increased more than ten-fold, and Essex was the third best-selling make in the USA and had a significant presence overseas, with an assembly facility in the U.K.

1929 was Essex’s high water mark, as it was for many manufacturers. The party atmosphere of the optimistic twenties (a prosperity not shared with everyone) was doused with cold water in the fall of 1929 as overextended investors, wild speculation, and unsound lending decisions came home to roost.

The “Great crash” of 1929 was frightening – markets lost 25% of their value in two days (October 28/29), but the real effects were not felt by most people until weeks, months, and years later. By the summer of 1932, the market had declined by 89% and the global economic crisis – which had many causes, not just the stock speculation – had become the Great Depression.

Theoretically, the Essex was well-positioned for a crisis.

It was less expensive than a Hudson when it was introduced but not a “cheap” car – but in the 1920s the Essex’s performance and prestige had grown as its price had shrunk – it was about 18% pricier than a Model A Ford and about 10% pricer than a Chevrolet. But boom times were on, and in 1930 the car was bigger and more luxurious than before. Essex slashed prices due to the economic circumstances, but the sales tumbled anyway.

But by 1933, the Essex name was gone, and Hudson never did figure out how to recapture that magic.

In the Beginning

Being a product of Hudson, the tale of the Essex begins with Hudson, and that story begins with the University of Michigan. There, in Ann Arbor, Roy Chapin (later Sr.), Roscoe Jackson, and Howard Coffin met for the first time. All three ended up working for Ransom Olds in the original incarnation of Oldsmobile in Lansing, Michigan.

At Lansing they were joined by another key player – Fred Bezner, who came to Olds from National Cash Register. All four liked Olds and really believed in the success of the products, but Ransom Olds was forced out in 1904 and the quartet soured on management thereafter, gradually leaving the company.

Chapin, Coffin, and Bezner were the first to go, taking a car Coffin had designed to the Thomas Company in Buffalo, New York, which became the Thomas-Detroit, then the Chalmers-Detroit as investors and relationships shifted. Jackson stayed at Olds until 1908, but quit to rejoin his old friends, bringing with him two valuable connections.

Chapin, Coffin, Bezner, and Jackson would build their own car independent of partners, and they wanted to do it in 1909. In casting around for financing, it was Jackson who brought in Joseph L. Hudson, his wife’s uncle, and George Dunham, another engineer from Olds.

Hudson owned the very profitable Hudson’s Department store chain – it was his name on the check and consequently the car. Dunham helped Coffin and Jackson engineer the new machine in secret. The car the group created became the very first Hudson in 1909. Chapin, then 29, was the architect of it all.

Hudsons were upper-middle-class cars and they didn’t come cheap, but they were a success both in sales and technical terms. In 1916, the company debuted the first Hudson Super Six, which immediately set racing and speed records. Foreshadowing a time in the distant future, a Super Six did a 102.5 mph mile at Daytona that year.

Hudson could not compete with larger makes on volume, however, even though its products were fairly popular. It did not have the scale of a Ford or GM. The success of the Super Six signalled to Chapin that more volume could narrow those economies of scale – so in late 1916, the company began figuring out a way to build a more modestly priced car in bigger numbers – that car would be the first Essex.

Hudson was only seven years old and the entire American auto industry only 20, in those days, all things were possible.

British readers will find this anecdote amusing – but when it came time to choose a name for the car, Hudson management looked at a map of the United Kingdom and chose “Essex” for snob appeal, according to historian Henry Austin Clark. Hudson set up a small subsidiary company for Essex and leased out an old Studebaker facility in Detroit to build the cars, but the war delayed the actual production until the fall of 1918.

Jackson was generally the overseer of the new Essex operation, accompanied by a new executive – A.E. Barit, who would later go on to lead Hudson. The first 90-or-so Essex cars were built that fall, but the real introduction did not happen until January of 1919.

The Rise of the Essex

A major publicity blitz was done for the “Series A” Essex early in the year and that first year neary 22,000 of the new cars were built. The car was conventional in almost every way and featured neither controversial nor innovative looks, but it had a very specific appeal – it was fast. The 55-hp F-head four was a real performer for the time and the Essex could cruise for hours at 50 or 60 mph, which was real speed for a moderately priced car in 1919.

This performance image was reinforced in early 1920 by a cross-country journey featuring four Essex tourers. Relief drivers were temporarily sworn in as mail carriers and each car carried a bag of mail. The cars made it from San Francisco to New York in an average of four days, 21 hours, and 32 minutes.

That isn’t cannonball stuff in 2020, but in 1920 there were virtually no highways and a large portion of the United States still only had dirt roads. Eat your heart out, Alex Roy.

Speed aside, the biggest single innovation at Essex was the debut of an affordable closed body car in 1921 for a 1922 introduction.

The Essex had offered a four-door sedan almost from the beginning. At $2650 in 1921 it was by far the most expensive car in the lineup. In those days most people preferred touring cars for two reasons. A. they were far less expensive to buy up front and B., flying glass is bad news in an accident and laminated safety glass was still not a common thing.

The 1922 Essex Coach reduced the cost of a closed body by using cheaper materials and less complexity in the body though it isn’t generally known how much Coffin changed to make it that much cheaper. It was $1,495 – “only $300 more than the Touring model!” shouted Motor Age. The car proved enormously popular and eventually got the laminated safety glass, which proliferated in the early 1920s.

Edsel Ford would later say that the Coach was Chapin’s gift to motorists everywhere. “He was the first one of us to realize the public wanted a closed car if they could get it at (a low) price. In very little time the rest of us were concentrating on closed jobs…” Who wouldn’t rather be inside during a Michigan winter rather than slogging things out in an open tourer with drafty side curtains?

The closed Essex was a bona-fide hit, and that year the subsidiary company was merged back into the parent, setting up the larger, better economies of scale Chapin had envisioned in the first place.

Essex never again innovated in quite the same way (though it was an early adopter of all-steel body construction, in 1927, but the cars went from strength to strength. In 1924 they gained an additional L-head six-cylinder engine that ran concurrent to the “fast four” into 1925. Jackson was still President of Essex then, and Hudson recorded a record $21M profit in 1925.

All through the 1920s buyers loved the Essex. In calendar year 1927, the public bought 210,000 cars. In 1928, 229,000, and in 1929, 227,000. In 1928, Essex had begun to infuse its performance-oriented machines with new styling not dissimilar to GM’s looks for the LaSalle. The cars also now had four-wheel mechanical brakes and even bigger versions of the six, now at 161-cid but still conservatively rated at 55 hp.

By then Jackson had passed away, Coffin was retired, and longtime Hudson exec William McAneeny was in charge of the burgeoning division, wiht Chapin still at the helm of Hudson.

The 1930 Essex

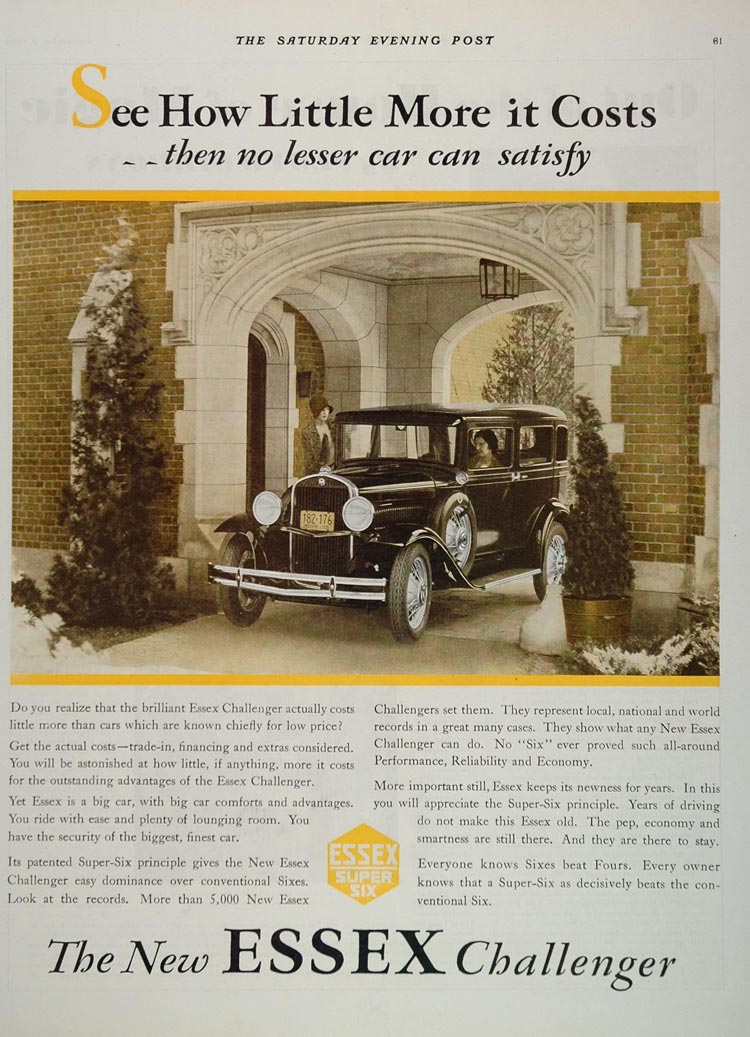

The 1930 cars were set in stone by the time the stock market began to crack, but anybody coming to the dealership was in for a great deal of value. With economic warning signs everywhere, the 1930 Essexes had their prices slashed and featured all-new styling and many more features than the ‘29 models. They looked bigger and richer, and they were.

The 1930 cars were five inches (12.7 cm) wider and almost four inches (10 cm) longer, with loads more chrome and pretty detailing. It had a brand new, lower and stronger chassis. It was only slightly heavier than the outgoing ‘29, and like that car bore the name “Challenger.”

A proliferation of new bodies meant more choices, but also more costs. The steel bodies were built by Essex itself, but wood-framed tourers and roadsters came from Biddle & Smart in Massachusetts.

It was clearly a car of the boom times, now discounted for the bust.

The 1930 model, which is the car seen in this story, was a great car but clearly the time was not right for a “bigger, fancier” Essex. Deliveries crashed to just 76,000 Essexes for the year.

1931 was no better, despite a horsepower bump and prices that stayed relatively flat – just 40,000 cars were sold on the year. Major restyling and mechanical updates were done in 1932 that made the Essex much more of a “Junior Hudson” in appearance.

During the year, Essex put a little more emphasis on the old performance chops, renaming a model the “Pacemaker” (a future Hudson name) and staging another cross-country cannonball, from L.A. to New York this time. The Pacemaker clocked the distance in just two days, twelve hours, and 20 minutes – but nobody was paying attention. Essex deliveries shrank to just 17,425 cars on the year.

By this time, the Depression was at its nadir and unemployment was at 23% – soon to crest at 25%. At the request of President Herbert Hoover, Chapin had gone to work as his Secretary of Commerce from August of 1932 to the end of Hoover’s term in March, 1933.

Chapin was a better car company executive than Secretary of Commerce, and it was one of his least successful endeavors, but he was also hamstrung by Hoover’s indifference and inabilty to come to grips with real problems. Most of his term was also served after Hoover had been defeated in the 1932 election, which meant little support for his work. He was no doubt relieved to return to Hudson when it was over.

Every manufacturer hurt badly in 1932, but especially those who could not compete with Ford, Chevy, and Plymouth on price.

To combat the Plymouth and take aim at the low-price biz, A.E. Barit and Chapin created the Terraplane for 1932, a lighter, smaller version of the Essex using the same enlarged 193-cid six that the ‘32 Essex used.

Terraplaning

Being lighter and smaller but still having the same engine, the “Essex-Terraplane” brought back a little bit of the hot rod image of the early Essexes, and it was the fastest low-priced car of 1932 after the V8 Ford. It quickly won a reputation as an agile and fast hill climber, winning the Penrose trophy at Pikes Peak.

Celebrity connections were also stressed – Amelia Earhart was Terraplane’s famous pitch person and the Terraplane name itself was meant to invoke the fashion and public feelings behind aviation (“When you’re moving fast in the sky, you’re aeroplaning, when you’re moving fast on the ground, you’re Terraplaning”). Superstar aviators like Earhart, Charles Lindbergh, and Eddie Rickenbacker – though his car company had long-since collapsed by that time – were feature of the era.

The effect of the Terraplane, however, was not to strengthen the Essex, but ultimately to supplant it.

Coming off a terrible 1932, only the Terraplane returned in 1933, with the Essex name dropped altogether. Hudson inherited the Essex Pacemaker, which became the reincarnated Hudson Pacemaker Super Six, with the original Hudson sixes having been dropped after 1929.

The Terraplane got larger and more powerful over time and closer to the Hudsons. The speed and style of the Terraplane were hard to match and helped Hudson weather the next few years, but it once again went upmarket, more like a Pontiac than a Plymouth. Eventually, Terraplane was also dropped – the car becoming the low-end “Hudson 112” in 1938. By then Chapin had died and A.E. Barit had stepped into his shoes. He would run the company until 1954.

Hudson did not revisit the idea of a smaller companion car until 1951, when it began work on the very different Hudson Jet. Essex, sadly, was not revisited at that time – it might have found some resonance with customers who were once again feeling optimistic in the early 1950s as memories of the Depression and Wartime austerity began to fade.