Zagato-bodied Alfas in the 1960s were built for speed. Although Carrozzeria Zagato was generally known for outrageous styling, much of it was modeled on function – Alfa’s TZ and SZ Giulias were beautiful, but they were track terrors. Swanning around on the corso was secondary. The car you see here, the Alfa Romeo Junior Z, was different.

Although the Junior Z was meant to eke out more performance from the already well-respected 105-series Alfa Giulia platform, it was also about style and exclusivity. Curiously though, the car was initially only powered by the smaller 1,290-cc twin cam from the Giulia GT Junior. The faster, slightly larger 1600 Junior Z came later.

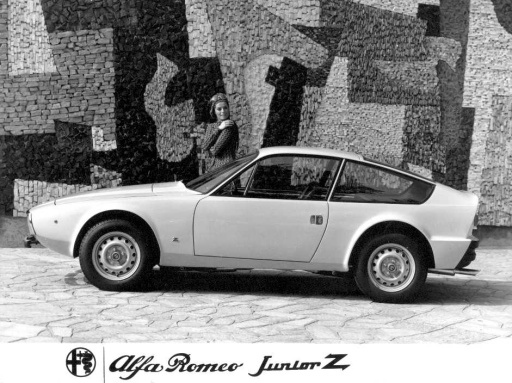

The styling was wildly futuristic in 1969 and not universally loved – but the wedge shape, penned by Ercole Spada, proved hugely influential over time and still looks modern today.

The car was one of Spada’s last designs for Zagato, capping the first decade of his long career. He departed in 1969 for Ghia, then Audi (briefly), before joining BMW in 1976 before joining Franco Mantegazza’s I.DE.A. institute in 1983. The Junior Z is also one of his personal favorites among the cars he’s had a hand in.

It was in production from 1969 to 1974, and arguably helped inspire Alfa’s next mass-market coupe, the 1975 Alfetta. The Junior Z’s story, however, starts the day Elio Zagato hired Spada.

Signore Coda Tronca

Spada was born in Busto Arizio, about 20 miles north of Milan, in 1937, and got his engineering degree from the Instituto Tecnico Feltrinelli in Milan, a school that still exists today. He was an artist as much as an engineer, and he loved cars. All through his childhood he drew cars on whatever paper or books he could get, no doubt to the annoyance of some of his teachers but to our benefit today.

After two years of military service, he applied to several Italian carmakers and design houses, but only one answered his letters – Zagato.

Elio Zagato, son of founder Ugo, interviewed Zagato one morning in early 1960 (possibly February) and hired him after asking just a few questions, including “Do you have a driver’s license?” and “Can you do full-size drawings?” He had a driver’s license but little experience with full-size renderings, no real training, and brought no portfolio with him.

Somehow, he got the job and within a few months was designing his first project for Zagato – the Bristol 406S, a design instigated by Bristol’s Tony Crook. Later that year, he designed a real legend – the Aston-Martin DB4 Zagato, arguably the most desirable Aston of all. Spada was 23 and instantly the brightest star in the style house’s stable of designers, though there was often little individual recognition at the time.

Thus was born a particular fertile period for both Spada and Zagato – the 1960s would be characterized by dozens of now-legendary designs, including the “Coda Tronca” Alfa Romeo SZ, an outgrowth of Zagato’s once not-factory-approved SZ racers.

Italian for “truncated tail,” many Spada designs were characterized by a kamm-tail look, though not all had the treatment in as stark a way as the SZ. The SZ was a race car, and the Kamm treatment improved its stability, but it also looked good on other vehicles.

The success of the revised SZ led to Alfa Romeo commissioning Zagato to rework the big (and relatively slow) 2600 into a sleeker and faster coupe, and it was Spada who designed this radical, wind-cheating machine. The 2600SZ, a slender fastback with a Kamm tail, was one of Zagato’s less-well-known efforts of the day, eclipsed by the Carrozzeria’s more well-known designs for Lancia. Just 105 were made, owing in part to its huge cost.

By contrast, Bertone’s effort on the 2600 Sprint (designed by Giorgetto Giugiaro), while slower, was much more popular and cheaper to buy. Alfa’s mainline coupe by this time was the very similar Giugiaro/Bertone-penned Giulia Sprint, offered as a 1.6 or 1.3L (GT Junior) car and briefly as a convertible, too.

The Junior Z Design

The 105-series Bertone-bodied coupes, four-seaters all, were good sellers for Alfa Romeo and potent track cars even early on – though in the mid-sixties they were often overshadowed by the bespoke racing versions, including Zagato’s TZ. But for ordinary street drivers, they were popular. In 1966, the company had also launched a popular new Spider variation of the 105, the Duetto.

Alfa Romeo’s managing director, Giuseppe Luraghi, thought the chassis could spawn yet another model – something even sportier, faster, and more exclusive than the 105 coupes, maybe a two-seater that would appeal to the crowd who bought Abarths and Giannini-tuned Fiats. At the 1967 Turin show, he approached Elio and Gianni Zagato about a collaboration.

Alfa was not alone, of course, in coming to Zagato for style experimentation. Lancia used Zagato very heavily for special models and concept ideas, as had companies like (as previously mentioned) Bristol and Aston. In 1967, Spada’s pen produced two concept cars that would directly inform the Alfa Project – the Rover 2000 TCZ and the Lancia Flavia Supersport Zagato.

Lancia already had a Flavia Sport Zagato – and it was one of Spada’s most eccentric designs. The Supersport was meant to take the Flavia into the 1970s and had been in the works for at least 18 months, it featured a razor-sharp wedge profile, upswept C-pillar, and raked rear with a snipped “Coda Tronca” in true Zagato style.

The Rover was much larger, clothing a full P6 chassis in a longer, lower interpretation of similar sharp-edged, wedge themes. Lancia was bought by Fiat before the Flavia supersport could ever see production (and Lancia didn’t have the funds to build it anyway) and Rover never really used the themes of the 2000 TCZ. Both cars, however, directly illustrated Spada’s thinking at the time, as did two concepts for Volvo – 1969’s GTZ 2000 and 1970’s GTZ 3000.

To create the Alfa, certain parameters were decided at the beginning of the project. It had to be something that was easy to produce in real volume, unlike the 2600SZ or the earlier TZ/SZ racers, and it had to use as many stock pieces as possible to keep the purchase price within the realm of the target market.

This last point seems rather contradictory, since there was little chance a bespoke, coachbuilt version of the Alfa would ever be “affordable,” and early plans included extensive use of alunum in the panels (which actually did happen, but in more limited form).

The basis of the Junior Z would be the 105-series Spider 1300 Junior, with a four-inch (10cm) shorter wheelbase than the 105 coupes. The rear of the chassis would be modified to suit the cropped tail of the car. Entirely stock drivetrain pieces were retained – and the car would be a Junior, meaning it would use the 1,290-cc Alfa Twin-cam exclusively, possibly again to keep the cost down and to keep taxes down, a factor for younger Italian buyers.

Very early sketches for the car included a continental-kit-like rear spare integrated into the Kamm tail, an idea abandoned pretty quickly. The tail got a very subtle curl at the end, essentially an integrated spoiler. Spada’s shape was an almost perfect wedge with a teardrop-like greenhouse.

The radical wedge shape was straight out of science fiction and so was the detailing – the car was almost totally unadorned and what details there were had the feel of a spaceship. There was hardly any chrome and the smooths sides flared out only around the wheel wells. The earliest prototypes had a slightly different rear treatment vaguely more evocative of the departed Giulia TZ.

The rear window could open a hair with an electronic actuator to allow for better ventilation – the Junior Z was a wind-cheater overall but drew very little air into the car.

The headlights were encased behind a plexiglass cover with an asymmetrical cut of ovals on one side, the traditional Alfa inverted triangle did not contain a badge – that was up on the hood. A big black bumper sat out back beneath a very plain fascia, a more delicate one up front.

The finished product was radical, and reaction to it was polarizing when it debuted at the 1969 Turin show. It was less radical inside, but you couldn’t not pay attention to it.

Alfa to Zed

The first chassis was delivered to Zagato in the summer of 1968 and construction of the prototypes began immediately. Zagato made the car production ready by the following fall. Aluminum was used in the doors and hood and few other places, but the body was made of steel. After the launch at Turin, at which no press materials or prep seemed to have been done for actual customers who wanted to order one, Zagato built about 200 cars and formal sales began in February of 1970.

It was around this time that Spada left Zagato for Ghia, now owned by Ford, a big promotion in some ways, but the end of a legendary collaboration. At Ghia, he worked on the Ford GT70 and certain other projects but it was never as good a union as his time at Zagato. He left for Audi in 1975 and then ended up at BMW a year later.

Production of the Z was a complicated affair, which in hindsight makes the decision to build it at all a strange one. Spider chassis were shipped from Alfa to Zagato, who modified them and then shipped them to Maggiora in Turin for body assembly. They were then shipped back to Alfa’s Arese facility for primer, then back to Zagato’s facility at Rho for final assembly. Serial numbers were all over the place, which confused restorers considerably later on.

With all the complexity and special parts, the car ended up fairly expensive and that limited how many buyers were willing to pay for it. For the slightly less money, you could have a much faster 2000 GT Veloce coupe or a 2000 Spider by 1972. It was quite a bit pricier than a Ford Capri, Opel GT, or Porsche-Audi 914 2-liter.

Those who did buy it, however, got what was basically a high-style concept car with practical, easy-to-service mechanical parts straight out of a regular Alfa.

The styling seems very bleeding-edge 1970s now, but it would be five or six years before those cues found their way into more mainstream production designs like the Triumph TR-7 or Alfa’s own Alfetta GTV (more on that in a bit). The Junior Z was, in 1969’s words, far out.

It drove and handled pretty much exactly like a Spider Junior, but a little more rigid. Of course, that’s what it was, a coupe Spider with different styling.

The lion’s share of production happened early, with almost 600 of the 1108 Junior Z’s built by the end of 1970, with production continuing into 1972. It wasn’t slow, either, but it’s price demanded more potenza for the prezzo.

So it was in 1972 that Alfa and Zagato enlarged the car slightly into the 1600 Junior Z, which bowed at the 1972 Turin show. It completely displaced the 1300 but preserved the styling almost exactly. It was slightly longer – to make production simpler the rear overhang was extended slightly. It also had a different front bumper; but it took an eagle eye to spot the differences. The 1600 used the 1,570-cc twin cam, now 108 hp (to the 1300’s 103hp). It gained only about 50 lbs. over the 1300, and was faster although not dramatically so.

The larger 1600 was not a big seller either, and 408 were made before things were called to a halt in 1973, with some leftovers selling into 1974.

The Long Shadow

With just over 1,500 cars built (plus a few pre-production chassis and a couple of factory rejects that were cut up by Zagato), the Junior Z was definitely not the success that Alfa or Zagato had hoped. Price and radical styling were probably the culprits.

However, not long after the 1600 ended production, a less radical but clearly related Alfa was being readied for production. That was Giugiaro’s Alfetta GT coupe, whose styling was finalized by Alfa’s own in-house team. The two cars don’t look the same, but the shapes are broadly similar and the details of the Alfetta GT/GTV integrated some of the thinking of some of the very last concepts that Spada did for Zagato.

Spada continued to work on the themes used on the Junior Z even after the car was finalized and two concept Volvos, both based on the Volvo 142 (the 2000 GTZ, 1969; and 3000 GTZ, 1970) directly influenced the Alfetta later on. The public liked this less radical wedge form, and the Junior Z went on to influence many other cars well into the 1980s and 1990s, including both generations of the Honda CRX.

The 1300 Junior Z and it’s 1600 successor were never exported to the United States, and were rarely advertised outside of Italy. Almost the entire run was sold domestically, though it was also ordered periodically in the Netherlands and Germany. The history of many individual cars is documented, in Dutch, by the Junior Zagato Archive.