Mercedes were purposefully meant to be timeless in the eyes of Daimler-Benz’s chief engineer Fritz Nallinger, but including the subtle fins on the new Heckflosse sedans forever linked the W110, W111, and W112 designs (collectively the “fintails”) to the 1950s.

Mercedes-Benz was never known for chasing trends, but it was probably unavoidable that the cultural impact of American designs would find its way onto the drafting tables of Stuttgart in the 1950s. Many other European manufacturers were also swayed by fins – BMC, Fiat, Peugeot, Rootes, and of course the European and British divisions of GM and Ford.

In style, Mercedes was hardly alone and its aesthetics were far more restrained than some others.

The six-cylinder W111 was the first of the fintails. It appeared in late 1959, a time when the look was still au courant, and was followed about a year later by the smaller, cheaper four-cylinder W110. They looked modern – but the real advances of the cars were far more than skin deep.

In a company driven almost entirely by engineering, the structure behind the fins was what really counted – and in that respect, the Fintails were far more advanced than most cars of their era.

They were designed around engineer Béla Barényi’s “safety cage” idea. When new, the Fintails were probably the safest and most comprehensively crash-tested cars in the world thanks to Barényi’s ideas, and they were marketed as such.

In this last respect, Mercedes bucked an American trend – and decided safety was worth advertising after they saw Ford attempt and fail to make safety a selling point.

All three fintails (the ultra-luxe W112 was added in 1961) were part of a program to rationalize the disparate Mercedes-Benz models of the 50s onto shared platforms. Barényi’s structural advances were common to all three.

Béla Barényi

Béla Viktor Karl Barényi was born in the Austro-Hungarian empire in 1907, the grandson of a wealthy industrialist (Fridolin Keller). Cars were still a new thing then, but Barényi’s grandfather had one – an Austro-Daimler. The Kellers were a wealthy family, and for the first ten years of his life, Barényi lived a charmed existence.

That was, of course, until WW1 destroyed Austria-Hungary and Keller’s industrial empire. It also claimed his father’s life on the front lines. Barényi went from a prince to a pauper, but his interest in mechanical things – sparked by Grandad’s car and time in his factories – never waned. He was interested in safety early on – developing a padded steering wheel for a sled he had as a teenager.

Barényi was educated at the Vienna’s Technische Hochschule (now known as TU-Wein or sometimes Vienna Technical College) from 1924, working on various types of engine and vehicle designs, at times having to seek help from the state to finance his education and apply for patents on things he designed.

Barényi applied to work early on for Dr. Ferdinand Porsche. He’d already designed whole vehicles in college, one of which would later prove a source of great controversy.

Porsche did not have work for him, and he ended up doing stints at Steyr, truckmaker Austro-Fiat, and Adler before coming to Berlin in 1934 to work on experimental vehicles. At each stage of his career, he was gradually made redundant due to circumstances beyond his control – just like his change of fortune due to the great war.

In Berlin he did not work for a manufacturer but for a kind of think tank, Gesellschaft für technischen Fortschritt (GETEFO, Society for Technical Advancement). He had many ideas there, including a car with a three-part safety body shell.

But GETEFO, who sent him to a similar organization in Paris (Société de Progrès Technique, SOPROTEC) for a time in the late 1930s, did not last, and he found himself unemployed again in 1938. He applied to Daimler-Benz, but was rejected. He was not deterred.

Months later he called in a favor from a friend he had met at Steyr a decade earlier. In 1929, he’d become friends with Karl Wilfert, who’d moved to Daimler-Benz and Sindelfingen not long after to become assistant to chief designer Hans Nibel.

Wilfert helped Barényi get an audience with board member and future Daimler-Benz CEO Wilhelm Haspel. This interview changed Barényi’s life and, it’s fair to say, the lives of many other people.

That morning he set out his ideas about the future of vehicles – a future he’d been working on for at least a decade. He detailed for Haspel how vehicles would be different in the future – different methods of construction, different priorities, different speeds – and different needs to keep occupants safe. No doubt, Barényi saw the interview as a once in a lifetime opportunity – he swung for the fences.

Listening intently to Barényi talk about his very advanced safety ideas, Haspel hired him that very day.

Supposedly, he told the engineer: “Herr Barényi, you will think 15 to 20 years ahead. Your work in Sindelfingen will be carried out in an ‘incubator’. Anything you invent will go straight to the patent department.”

There he would toil in relative obscurity for a long time. Early on, he invented a disappearing windscreen wiper that hid beneath the hood when not in use. Daimler eventually used it – in 1980.

But some of his innovations did reach production fairly quickly – he designed the frame of the 170V, which was much more rigid than its predecessor. Flat pans gave way to reinforced rippled designs, more rigid and quieter too.

After the War

After the war, he was dismissed for Daimler for having a past association with the Austrian NSDAP, Austria’s Nazi party. Allied regulations required dismissing him, although it’s generally conceded that his involvement in such activities was minor and may have been linked to attempts to get jobs (unconfirmed) in Austria.

In attempting to find work with Porsche, Barényi may have shown Porsche ideas for a small car he’d been developing since University – a small, rear-engined car. He also contributed to a magazine – Kleine-Motor-Sport, later Motor-Kritik, edited by another engineer and fellow Hungarian – Josef Ganz. Both Barényi and the Jewish Ganz presented ideas in that publication that were very similar to what Ferdinand Porsche came up with for the Volkswagen, and no doubt the two were well acquainted.

One of the earliest prototypes along the lines of the Volkswagen was Ganz’s “Maikäfer” in 1931, and a production car, the Standard Superior, similar in some ways to the VW, evolved from Ganz’s ideas, as did a prototype from Zündapp. By 1934, when Ganz was hounded out of Germany by the Nazis, Barényi’s designs had also been showcased in the magazine.

After the war, the Volkswagen was revived and there was considerable legal acrimony about who actually invented it. Ganz, Tatra’s Hans Ledwinka, and Barényi were all drawn into that controversy and all had substantive claims for actually having developed the concept.

As early as 1925 Barényi had designed a light, rear-engined, air-cooled, boxer-powered small car, and Porsche knew it. In the 1950s, two books ridiculing Barényi’s invention and claims of influencing the Volkswagen stirred enough public controversy for Barényi to sue the authors – and win. But he never formally claimed any ownership of the design or sued VW. Ledwinka, on the other hand did, and also won his case.

We’re getting ahead of ourselves, however.

Back to Mercedes

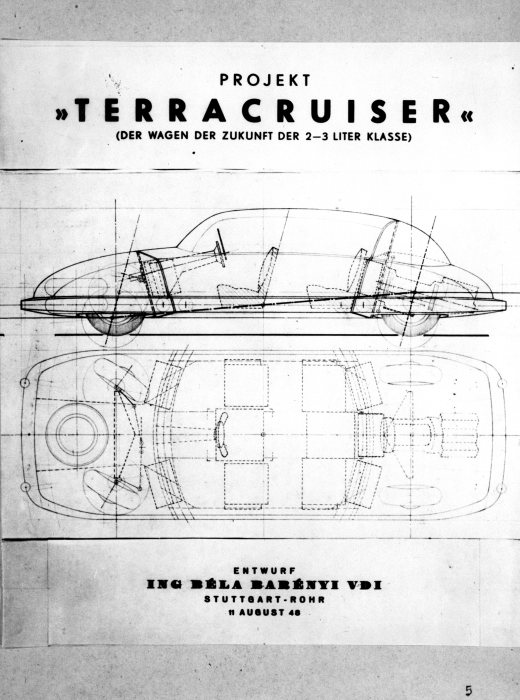

It was two years before was re-hired after the end of the war. In that time, he developed another safety vehicle idea, the six-passenger, rear-engined Terracruiser, with central seating for the driver and a shell designed to absorb impacts.

The Terracruiser combined an extremely rigid safety cell in which the passengers were located with more deformable outer shell materials – which would absorb most of the impact rather than transfer it to the passenger. A rigid shell would hold up better, too, if some of the impact were absorbed before it got to the central area of the safety cell.

In 1948, he was formally rehired and put under Wilfert’s charge as the company’s first dedicated safety engineer. After returning, many more of Barényi’s ideas worked their way into the “Ponton” Benzes, which had an ancestor of his famous crumple zones.

In the early 1950s, during the Ponton Era and the VW kerfuffle, he continued to refine his idea for the three-part safety chassis. Barényi’s time to shine came in 1955-56, when development work began on what would become the next generation of Mercedes mainstream models.

The “safety cage” concept from the Terracruiser would baked into what became the “Fintails” from the start. Barényi directly participated in development of the chassis and body, and the company modeled the idea loosely on his 1952 safety cell patent.

Designers, the exterior was led by Karl Wilfert, worked from the inside out around the safety cell and crumple zones – designed to absorb impacts rather than transfer them to the occupants. The cars also had new retractable seatbelts, another Barényi creation (he would ultimately have more than 2,000 patents).

The cars also had padded steering wheels, padded dashboards, more swept area in their new “clap hands” windshield wipers, recessed door handles and instruments – the whole car was thought out with impact safety in mind.

The cars were, of course, not just meant to be safety cars – they were developed to drive and handle well and mostly used updated powerplants from the Ponton era – developing a whole new platform, even at Mercedes, costs a ton and manufacturers generally re-use at least something to keep costs down. In Mercedes’ case, it had excellent engines to draw on.

Wilfert’s stylists aimed for conservative and got it, with the addition of the tiny fins even having a practical use – you could see where your car ended when parking.

The cars were not crash tested until they were nearly production ready in 1959 – but the tests bore out Barényi’s concept. The car absorbed the impact and kept its (dummy) occupants safe.

The crash testing of the Fintails ultimately resulted in a full crash research facility coming online at Sindelfingen and further exploration of safety ideas.

Selling Safety

Daimler-Benz had been carefully watching other manufacturers (and academics) experiment with crash safety for some time by then. In 1955, Wilfert, Nallinger, and competition man Rudolf Uhlenhaut had traveled to Ford’s proving grounds in Michigan and observed crash testing there.

In 1955, Ford had publicly presented an ambitious plan for improving passenger safety, including padded dashboards, seat belts, collapsible steering columns, and safety door latches. Ford had made some of these things optional by 1956, and tried hard to market them that year and in 1957 – to no avail. The public was not particularly interested and Ford dropped the idea.

A decade later, they wished they’d stuck with it when safety legislation and the creation of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration made such things mandatory.

Mercedes, however, decided that such advances were a selling point if they could be demonstrated to work, and the Fintails were very good at that. By 1960 the crash test dummy (made by the American company Alderson Research in Cleveland, Ohio) even had a name – Oskar.

Starting in April of 1960, the press were invited to see the tests. Anybody who’d seen a serious car wreck in 1960 could immediately see a difference in how the cars functioned. Only Volvo was making such a similar commitment to demonstrating safety at the time.

The Fintails were a huge success for Mercedes, but even though safety was one of the primary purposes of the design, they sold as much on durability and luxury as they did on anything else.

The bigger W111/W112 cars, which also featured stylish coupes by Paul Bracq, were de facto luxury machines but it was the smaller W110 – seen here – which sold in volumes.

Big volumes – more than 628,000 were made in Germany, more than half of them Diesels. Passengers getting off a DC-8 or 707 at Tempelhof, Ellinikon, or Kloten could find a long line of 190/200D cabs waiting for them.

In the USA, the cars were distributed by Studebaker before the creation of Mercedes-Benz USA. Though diesels, popular abroad, were a hard sell in America, it was the Fintails that first made serious inroads in the U.S. market.

The W110 models, the cheaper versions, were built in two series from 1961 to 1968, with the changeover from series 1 to series 2 happening in July of 1965. The early cars used either the M121 2.0L gas four or the OM621 diesel four – both reliable, tough engines. The second series gained an optional M180 2.3L six. All were veteran powerplants, and like the cars, built as if they were hewn from solid rock.

Barényi’s innovations kept coming, with designs of his creation entering production long after he had officially retired in 1972.

Nice write up. Good information also.

Goodwork