In the 1970s, the Supermini was king of European car dealerships, and the Fiat 127 was arguably the first of the breed. The new wave of space-efficient front-drive small cars traced back to the Mini and ran through BMC’s ADO16 cars, Peugeot’s 204 and 304, and Simca’s 1100, but it was Fiat that found the modern Supermini formula first, if only just.

The blue car you see above is a SEAT 127, but the Spanish-built versions were almost identical, at least early on in three-door form. Hot on the heels of the 127, which was launched in April of 1971, were the Renault R5 (January, 1972) and Honda Civic (July of ‘72), and the R5’s default hatchback body may have made it the first de facto Supermini had no Fiat hastily added a hatch to the 127 for its sophomore outing.

By 1974, Fiat had sold more than 1,000,000 127s and a host of similar cars began popping up. Peugeot’s 104, Audi’s 50 (which became the VW Polo), and GM’s rear-drive T-car Opel Kadett were all on the market by the end of that year, and Ford was knee-deep in developing the Mk1 Fiesta. Not coincidentally, it was Spain’s most popular car in the 1970s, and Ford chose Spain to build a new manufacturing facility for the Fiesta.

The 127 did not come to the United States, so there isn’t a North America-centric history of it, but it had a huge impact on the European market and remained in production until 1996 in South America, primarily being produced in Argentina and Brazil (but also Colombia, Uruguay, and Venezuela).

The story of the 127 starts, as modern transverse front-drivers do, with the Mini.

A Better Front-Drive Mousetrap

The Mini arrived around the time of Dante Giacosa’s “Project 123,” a study of various ideas for future Fiat’s conducted primarily at the company’s research arm, SIRA (Società industriale ricerche automobilistiche or Automotive Industry Research Company). 123 evaluated both front-engine, front-drive models and rear-engine, rear-drive models.

The front-drive 123 ideas went nowhere. though the prototypes got to fairly advanced stages. They were too complex, and the Mini’s success sapped Giacosa’s enthusiasm for the project. The 124 was engineered mainly under Oscar Montabone, a Fiat man recalled from time at Simca in 1963 to create a more conventional car.

Dante Giacosa, of course, was the genius behind most of the Fiats built from the 1930s until his retirement in early 1970. It was Giacosa who steered the creation of the classic Topolino 500, the 1100, the 600, the Nuova 500, and lots of other highly successful Fiat designs. He also oversaw the creation of the meccano-like engines and platform pieces that made Fiats so cheap to build and have such high levels of parts interchangeability.

When the Mini hit showrooms, Giacosa immediately regretted not having spent more time on front-drive research.

In 1947, he’d engineered a small transverse front-drive experimental car similar in some ways to the Mini, but had let the idea drop on the basis that putting the gearbox into the sump made for a less-than-durable gearbox and a costly production process. The Mini had a slightly more sophisticated setup, and Giacosa loved it, but still judged it to be a very costly car to build.

As it turns out, he was correct in that assessment, but his next step, while Project 123 was still going on, he started designing a front-driver that improved on Issigonis’ ideas and his own 1947 concept.

Carlo Salamano, Fiat’s longtime head of testing and often described as the “technical conscience” of Fiat, disliked front-wheel drive. Salamano officially retired in early 1962, but remained a consultant, and he had management’s ear. Giacosa had to work very hard to overcome his objections, but eventually Fiat’s general manager, engineer Gaudenzio Bono gave the green light to “Project 109,” which became the Autobianchi Primula.

Giacosa saw many ways to utilize a transverse setup to make a car as space efficient as Issigonis had, but the key was separating the gearbox and making it something that could be produced as cheaply as a conventional car. Instead of mounting the gearbox below or in front of the engine, Giacosa wanted to mount it on the side – a conventional rear-drive layout turned sideways.

The actual gearbox mechanisms were designed by Ettore Cordiano. For months the team could not figure out how to mount the gearbox on the side of the engine without making the car considerably wider, which would add weight and complexity.

By developing a concentric clutch mechanism, Cordiano eliminated the conventional thrust bearing and lever. That meant a physically smaller gearbox and no need to widen the car. The driveshafts were unequal in length but balanced to try and eliminate torque steer. The Primula did not have an overabundance of power, so that wasn’t that much of a factor. It also required some reworking of the brake balancing.

The first tests of the “109” were conducted in November of 1963 and even won over Salamano. The car used Fiat’s conventional 103-series engine and wasn’t particularly exciting, but it worked pretty well. It used a big hatchback body designed by Felice Mario Boano and his son Gian Paolo, another forward-thinking move.

But it was a radical departure from conventional Fiats, and if it failed, the consequences could be high. Instead of building it as a Fiat, Giacosa and Autobianchi director Nello Valecchi proposed to Bono that it be an Autobianchi instead.

Autobianchi, Fiat’s joint venture with Bianchi and Pirelli, sold only upscale versions of the Fiat 500, and the Primula would allow it to expand while providing a testbed for Fiat’s front-drive ideas.

It was easier to service, longer lasting, and quieter than the Mini’s gearbox, though the trademark gearbox whine of later designs based on the Primula tells you that it wasn’t 100% perfect. Still, it was the first modern transverse front-drive car with a side-on gearbox, the arrangement virtually all front-wheel drive cars use today.

Once the Primula proved a reliable, easy-to-build success, the race was on to take the idea and turn it into the next generation of Fiats, which would be more efficient and better packaged as a result.

The X1-Files

The most pressing need in Fiat’s portfolio in the late 1960s was a replacement for the 1100, first introduced in 1953, so it was this size of car that got the attention first. Project X1/1 would be the forefather of an entire new generation of Fiats and arguably the first modern Fiat small car. It became the Fiat 128 in 1969.

Project X1/2 would be a direct response to the Mini, the Autobianchi A112. Project X1/4 would be the replacement for the Fiat 850, which became the Fiat 127. In this new development scheme all subsequent Fiats (and some Fiat relatives like the FSO Polonez) in the 1970s would have “X-codes.” Project X1/3 was the big 130, Fiat’s 1970s flagship.

The development of the 127, A112, and 128 were all interlinked. The 128 would replace the 1100 and use an all-new engine family developed by Fiat’s motor ace, Aurelio Lampredi. Cordiano, meanwhile, was put in charge of the car design offices in 1966 and was heavily involved in all of the designs, while Giacosa (and Montebano) oversaw the entire vehicle engineering operation.

Originally Giacosa had in mind just the X1/1 and X1/2, with the “2” to be built as a Fiat. Gaudenzio Bono, however, still second in command at Fiat (since 1966 to Gianni Agnelli himself) decided that the ideas could be spread even further.

The X1/2 would be broadly similar to the X1/1 but scaled down to Mini size. It would utilize the old Fiat 100-series OHV engine inherited from the 600 and 850 and sold as an Autobianchi. For Fiat’s smaller car that would directly replace the 850, the X1/2 mechanical pieces would be adapted into a larger body, but not as large as the 128. That’s how the “tweener” Fiat 127 was born.

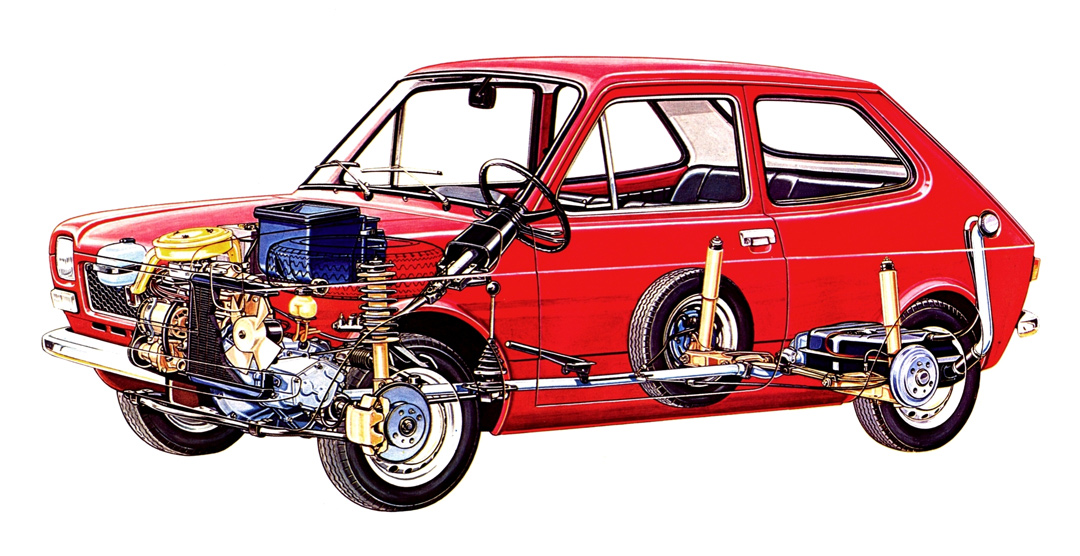

The 128 was the first and most important of the set, but both it and the A112 arrived at the same time. Though Simca had some of the same ideas around the same time or earlier, the 128 was a landmark car in that to modern eyes, the mechanical spec would still seem fairly familiar. The recipe was simple and widely imitated afterward: Front drive, side gearbox, MacPherson struts with coil springs all around.

The 127 would be a little different. It was meant to be cheaper to build and buy, which meant that while the forward half of the car was a close relative of the 128, it got a simpler transverse leaf spring suspension in back, though it didn’t make it any less of a keen handler.

Launched in April of 1971, about 18 months after the 128 and A112, the 127 was in a sense something really new. It was a family-oriented two-door car like the 850 had been, but was far more space-efficient. Thanks to Bono’s suggestions, it was a bit bigger than cars like the Mini or A112, but smaller than the BMC ADO16-sized cars like the 128 or Alfa-Romeo AlfaSud. There had been cars of its size and price before, but none that used the modern side-on transverse setup.

Originally, the 127 was set into the world as a two-door fastback with a trunk, but a proper hatchback was added for 1972. That year the 127 was joined by the Mk1 Honda Civic and Renault R5, two cars of similar concept and size. All three had a seismic impact on the small car market, and kicked off the class known as “Superminis.” Within half a decade, almost every manufacturer had one.

The R5, with a traditional north-south front-drive setup, was the 127’s biggest competitor in Europe, and both cars were conceived around the same time. Both were big successes, but not without a certain note of tragedy in their beginnings.

Pio Manzù

The friendly, characterful lines of the Fiat 127 were distinctly different from the square, almost industrial-looking 128 and the classic sixties style of the A112, and that was because it was largely shaped by a designer from outside of Fiat’s system, Pio Manzù.

Born Pio Manzoni in Bergamo in 1939, Manzù changed his name for professional purposes. He was the son of a famous sculptor, Giacomo Manzoni, and a talented artist and thinker from a young age.

He earned a place at the prestigious Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm, a design school, in the early sixties and there he and some friends designed a kind of proto-mininvan/tall-MPV, the Glas / NSU Autonova FAM Concept. A prototype was actually constructed thanks to interest from NSU.

Manzù preferred designing utilitarian objects to decorative or sexy ones, and early in his design career he created the Chrono clock for Alessi and the Parentesi lamp for Flos, a collaboration with architect Achille Castiglioni.

Fiat Centro Stile, by 1968 run by Gian Paolo Boano, was busy with an armada of projects in the late 1960s and Giacosa was so impressed with Manzù’s work that he brought him in as a consultant. But the higher-ups felt that the 28-year-old Manzù wasn’t experienced enough to take on whole projects. Giacosa assigned him a concept car that used some of the themes of his MPV, 1968’s Fiat City Taxi.

Based on the 850, it had a tall and narrow body with sliding doors, a micro-sized minivan with clean lines. Well liked in the studio, the concept convinced management to trust Manzù’s abilities, and Boano and Giacosa tasked him with the aesthetic direction of X1/4. Manzù’s shape was user-friendly and utilitarian but good looking, and went into production with only minor changes.

However, Manzù wasn’t around to see its success. Manzù personally shaped the clay model of the full-size X1/4 presentation, and it was due to get an evaluation from upper management on May 26, 1969, a Monday.

Over the weekend Manzù had driven his Fiat 500 home to see his parents in Bergamo, and on the way back on late Sunday night, he lost control of the car and was killed in the crash. He was only 30. The team at Centro Stile were heartbroken. All through the prototype’s hood was a little too bulky, but Boano himself changed it for production only reluctantly.

The car was subsequently developed for production more or less how Manzù had designed it aside from the slightly lower hood line, and appeared in the spring of 1971 as a finished product. It was an immediate success and earned Fiat the 1972 European Car of the Year Award, a follow-up to its 1970 win for the 128. The Renault R5 came in second in 1973, and its principal designer, Michel Boué, died of cancer before that car came to market.

Life of the Fiat 127

The first series 127, our primary focus here, continued almost unchanged into 1977. The hatchback addition for 1972 was a major plus, and most customers preferred the much greater utility of the “tre porte.” All of the Mk1 127s used the 903-cc OHV engine, which wasn’t particularly powerful but was rock tough and good on gas, which became an especially important point just three years after the 127’s launch when OPEC 1 happened.

The car was relatively basic, and built for mechanical durability. All were four-speeders and there were no power accessories. It was much larger inside than it looked, and could seat four in reasonable comfort if the rear passengers weren’t too tall. It’s low price and frugality made it very popular, and the 1,000,000th 127 was built just three years into production.

The mortal enemy of these cars, as with many Italian cars of the era, was rust. Even the blue SEAT in our period photos, probably no more than four or five years old at the time, is sporting some rust.

SEAT, Fiat’s then-long-running Spanish partner company, began assembling the 127 soon after it launched in Italy. As in other less protectionist European markets, the 127 was a huge hit in Spain and it’s most popular car for several years. SEAT diverged only a little from Fiat’s original design, but improved it in material ways.

The SEAT 127 got a five-door variation before Italy did, and it also got a unique-to-SEAT 1,010-cc version of the old 100-series OHV engine. It was developed in Spain before Fiat expanded the engine range of the Italian-built 127s. 1,238,166 SEAT 127s were built from 1971 to 1982, and it got the same updates in later series as the Italian versions.

In 1977, the Series 2 debuted with a heavy facelift and an optional 1,049-cc engine. From 1978 there was also a 70-horsepower 1,049-cc unit sold as the “Fiat 127 Sport,” and a high-cube van, the Fiorino, body style. The body range was also expanded to include four-door models, which had first been seen in Spain.

The Series 2 ran into 1982, before a run-out Series 3, finally featuring the SOHC engine family created for the 128, debuted to mark time before Fiat could finish up the Uno, its next best-selling supermini. The 127 was not sold in North America, but it was a global hit, with production continuing in South America until 1996.

Editor’s note: Unlike our normal posts, this one uses mostly manufacturer images, though the blue SEAT 127 is from the OldMotors archives. Due to the Coronavirus pandemic, travel has been off for a year now, which interferes with our ability to gather photos, particularly of vehicles not common in North America. We’re doing our best!