Sometimes a car is less significant for what it is than what it represents, and the original Mercury Tracer definitely falls into this category. Although it had a Ford sibling, the Asia-Pacific market Laser, both the Tracer and that car were just lightly restyled versions of Mazda’s circa-1986 BF-Series Familia, better known in the USA as the 323. It was a perfectly pleasant car just like its Mazda sibling, but where it was built was a much bigger deal, or it would be later on.

The Tracer was the first car to be built in Ford’s sprawling factory in Hermosillo, Mexico. The product of a long chain of circumstances, Hermosillo wasn’t Ford’s first factory in Mexico, but it was the first high-profile Big 3 plant there to export cars to the USA in real numbers. Even then, Hermosillo was just one set, and the Tracer just one actor, in a long telenovela of production, capital, and trade.

Thanks to Presidents Reagan and Bush 41, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) would make Hermosillo a blueprint for many more cross-border factory operations filling U.S. dealerships with cars made in Mexico, but that was still in the future when the initial negotiations to open “Hermosillo Stamping And Assembly” happened in 1983.

La Década Perdida

The story starts with OPEC. Two successive Mexican Presidents—Luis Echeverría Álvarez and his hand-picked successor, José Lopez Portillo—had both badly mismanaged Mexico’s economy. Inheriting stable growth, they poured money into pet projects for connected people—particularly in the oil and gas industry—and borrowed heavily from foreign banks to do it. By 1981 the Peso was wildly overvalued, oil revenues plummeting, and the economy in tatters.

The mismanagement of the Portillo era concluded with Mexico defaulting on its sovereign debts in the summer of 1982 and a lost decade of economic growth, later called La Década Perdida.

The subsequent regime of Miguel de la Madrid had to go about trying to rebuild the economy and get over the damage with limited credit resources, so it was going to do everything it could to stimulate industry in a more balanced way.

At the same time, Ford and Mazda both had their own brushes with fiscal death. Mazda, caught out by OPEC during the Rotary era, was bailed out by Sumitomo Bank, who helped arrange a cash infusion from Ford. Ford, posting huge U.S. losses from 1978 to 1982, relied mostly on Ford of Europe to keep the ship above water in those years but recognized a bargain when they saw one. Dearborn took a 25% stake in Mazda in 1979.

The two companies had collaborated since 1971, and with this more formal partnership, they could go further on platform sharing and production. The Laser grew out of the same kind of setup as the earlier Courier pickup had.

Ford’s losses had resulted in many plant closures in the USA, and they also forced the company to examine how it made cars domestically more closely. One reason why the 1981 Escort differed so dramatically from its European Mk3 counterpart was that many efforts were made to make it cheaper to build. In 1982, the Escort was doing very well, but Ford still found it didn’t make much profit on it, and for the next North American Escort it wanted to look to Mazda for joint development, just as it was doing with Mazda and Kia at the time.

The Free Traders

One of the few things that had gone well for Mexico during the Portillo era was the production of vehicle engines. Mexico’s trade entreaties to the Carter and Reagan Administrations had convinced the Big 3 to source more engines from Mexico, and Ford constructed an engine plant in Chihuahua to build Mazda engines in 1982. Nissan, VW, Chrysler, and GM were all importing hundreds of thousands of Mexican engines to the USA by then.

At the same time, President Reagan made free trade a fixture of his 1980 election campaign, with his original concept being a free-trade zone that would encompass the entirety of the Americas, not just the U.S., Mexico, and Canada. Thus, the automakers had an ally in Reagan in making investments in Mexico that would theoretically pay off when a free trade act was passed. The first step, however, was updating the United States’ trade agreements with Canada.

Up north, trade ministers had also been advocating for freer trade with the U.S. since the mid-1970s, but didn’t find a receptive audience until the mid-1980s in the form of Canadian prime minister Brian Mulroney. Though Mulroney had not been a free trader and had opposed such ideas until 1984, he came around about a year later and talks for the 1988 Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement (CUSTFA) began.

Reagan warmly embraced the Canadians, as it helped him further his free trade goals, but the Canadian public remained divided, and in fact 1988’s Canadian general elections saw an outpouring of opposition. Mulroney’s conservatives, however, won a narrow majority and approved the deal.

Engines of Industry

Meanwhile, in Mexico, the new engine plant was successful enough to justify exploring the possibility of building a full assembly plant somewhere else in the country. Where? Somewhere far from Mexico City and the existing Ford of Mexico factory, which was slow to change and an area where labor costs were among the highest in the country. Ford built plenty of cars for Mexico there, many of them small variations on U.S. models, but it felt it needed a new facility to expand to make all of its U.S. small cars south of the border.

Initially, sites in San Luis Potosí (today home to many factories including BMW’s Mexican operation) and Ciudad Juarez (now a major supplier center, including companies like ZF) were considered, but from the mid-1970s until a major industrial exhibition in 1981, the state of Sonora had been trying to accumulate interest from investors. It had worked, and there was already an American-backed industrial park in Hermosillo. In 1982, Mexican Ford megadealer Guillermo Tapía approached Sonoran Governor Samuel Ocaña Garcia about putting in a bid for the city.

Hermosillo was well placed geographically—200 miles from the U.S. and near the recently-expanded port of Guaymas. It was also a growing city with a willing workforce, and Sonora would put in 3 Billion pesos of infrastructure upgrades. In the climate of 1983, with Ford only just back in the black, negotiations began to build a factory there.

The United Auto Workers (UAW) union was not pleased by the Big 3’s acquiescence to Mexico’s engine demand, but they had little choice. President Reagan regularly met with Portillo and de Madrid and saw the demand as mutually beneficial. In 1984, Reagan’s Democratic challenger, Walter Mondale, and running mate Geraldine Ferraro, had warned union workers about the potential impacts of Reagan’s anti-union and free trade policies, but hadn’t been able to overcome Reagan’s star power.

Of course, part of the advantage of Free Trade is that it allows companies to place factories in locations where wages are lower, reducing the leverage of single-country Unions. There was some consolation, however. Mazda and Ford were planning to open a huge new Union factory in Flat Rock, Michigan, and Ford promised to expand domestic production of the then-new Ranger pickup, a promise it kept by building Rangers in Louisville, Kentucky and St. Paul, Minnesota.

Ford Laser to Mercury Tracer

The announcement came on January 10, 1984. Hermosillo would open in late 1986 and build 130,000 “Japanese” cars a year. The car would be the BF-series Familia, or rather, the Laser, created for Australia and not sold in North America, at least not yet. It would have very light interior and exterior upgrades and be badged as a Mercury.

Although the cost benefits of NAFTA still lay in the future, sourcing the car from Mexico was also a convenient end-run around Japanese import quotas that affected Mazda’s supply of U.S. models. Trainees assembled and disassembled prototype Tracers throughout the summer of 1986, even before the Hermosillo complex was completed.

Mercury dealers, who’d had the slow-selling Lynx as their competitor for everything from the Honda Civic to VW Golf, would now sell the Tracer instead, with deliveries to begin in the spring of 1987.

While Ford had huge success with the Escort, earning the “best selling car in America” honors in 1982, 1987 and 1988, the Lynx was a dud from the start that had never really found much of a market. Mercury was a middle-class brand, or at least it pretended to be, and the Escort was an odd fit. The Hermosillo car, Ford hoped, might do better.

The Tracer was fundamentally a Mazda, but that was no bad thing. The fifth-generation BF-series Familia, introduced in early 1985, was roomy, handled well, got good gas mileage, and was even fun to drive in the best Mazda way. It wasn’t fast or particularly spicy to look at except in Turbocharged AWD GTX guise, but that particular configuration would not be available in the Tracer.

Tracers would come with just one engine, Mazda’s B6 1.6 liter four with 85 horsepower, mated to a five-speeder or a 3-speed automatic. The Tracer’s equipment levels were about equal to the higher-spec Mazda versions, which were already on sale and getting good reviews in the USA as the Mazda 323. Where the main U.S. 323 model was a sedan, the Tracer would come only as a hatch or a wagon, and three-door models would be built in Hiroshima by Mazda. Canada, with its huge network of Mercury dealers, would get all of its Tracers from another foreign subsidiary: Ford Lio Ho of Taiwan.

Qualitatively, there was no difference between the Japan-sourced and Mexican-sourced cars, which spoke well to Mazda’s assembly process, which was implemented at Hermosillo with careful observation from Ford.

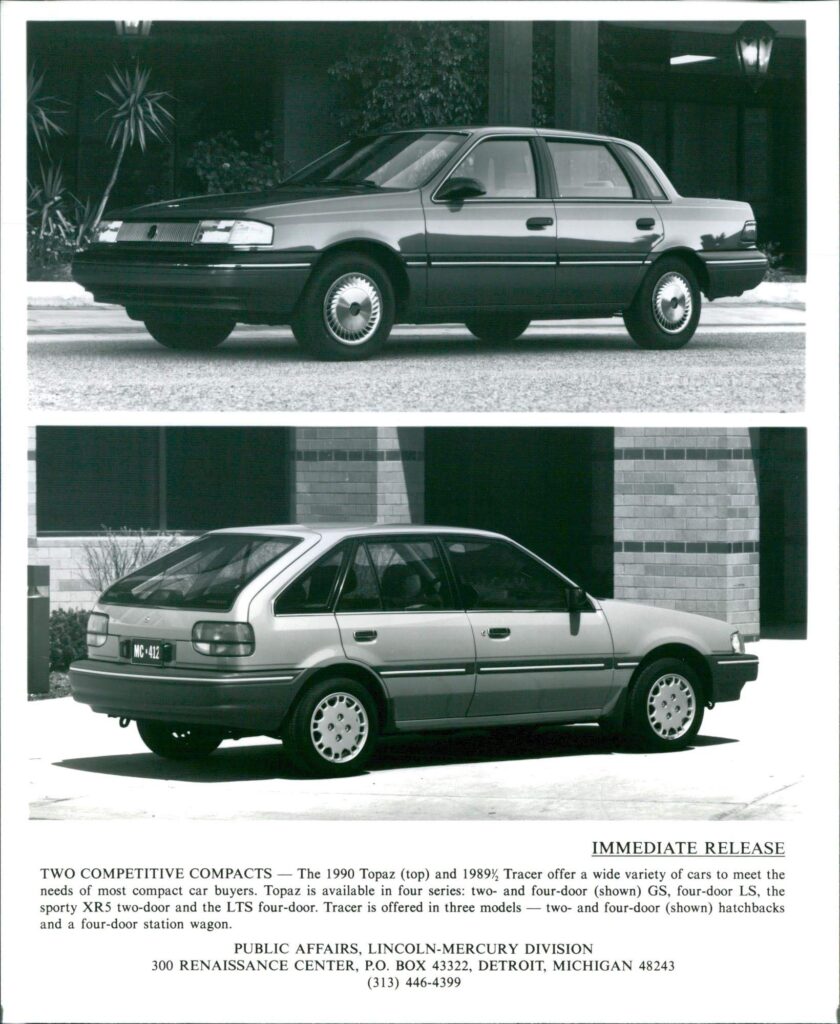

Mercury didn’t do too much marketing for the Tracer, which only ran for three model years plus a “1989+1/2” run out, but about 140,000 of them were sold in that time. The Mazda cars did not displace the big-selling domestic Escort, whose profit margins improved over time. Instead, Ford kept that car going into 1989, ultimately replacing the first-gen Tracer and the Eighties North American Escort with new cars in 1990.

The Tracer helped with those, too, as the collaboration on the Laser and Tracer essentially paved the way for a U.S. Escort (and a second-gen Mercury Tracer) that used Mazda’s BG-Series Familia platform as a basis but with styling done by a Domestic Ford team. During the era of those cars, both Escorts and Tracers would be built in Hermosillo, as would the Ford Focus that replaced them.

Hermosillo Stamping brought with it almost a billion dollars of investment to the surrounding area, most of which went to suppliers, which in turn made Mexico an even more attractive prospect for auto manufacturing. That’s how manufacturing efficiencies work — the more things you can do in an integrated way, the cheaper those things are to do and the more efficient the production system.

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) essentially turned the U.S.-Canada free trade system into one that also included Mexico. This agreement was largely negotiated and finalized by Reagan’s successor, George H.W. Bush, and passed with Republican majorities voting for it in both the U.S. House and Senate in 1993 and President Bill Clinton signed it into law. As in Canada in the eighties, opinion was mixed. In the 1990s, a small majority of Americans thought NAFTA was good for the U.S., but those numbers reversed in the 2000s.

In 2019, Mexico exported $52 Billion in vehicles, with about 73% of those cars heading north. The plant made its last car, a Ford Fusion, in 2020, but it’s still making Mavericks and Bronco Sports. NAFTA integrated all three economies to a considerable degree, and the supply chain today features millions of parts that are shipped between all three countries in multiple stages, sometimes via air freight for speed. This is only made possible by the tariff-free nature of this system, which would otherwise hugely increase the cost of goods made in all three countries.

The original Mercury Tracer may be a largely forgotten part of this free-trade story, but a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.

Thanks for sharing this very interesting history!