Today our feature car is a 1960 Panhard PL 17, a highly unconventional car with its origins in the 1940s and the imagination of talented French engineer Jean-Albert Grégoire.

But to really understand where it came from, we’ve got to go back even further than Grégoire’s wartime work with Aluminium Français, further back than Grégoire’s lifetime itself. All the way back, in fact, to 1880s and the founding of the House of Panhard.

Panhard et Levassor was originally a woodworking machinery firm called Périn et Pauwels, but in 1887, when Périn died, control passed to René Panhard and Emile Levassor. Levassor’s new wife was the widow of Edouard Sarazin – the first man in France to acquire a license to build the Daimler Motorwagen.

By 1891, they’d built their first car – but it wasn’t a straight copy of the Daimler. It used the Daimler V-twin, but mounted it up front with a sliding-gear 4-speed in the middle, driving the rear wheels. Panhard invented the FR layout, the Systeme Panhard.

Thus began a long and glorious history of Panhard cars which, before WW1, were considered some of the finest mainstream cars in the world. Along with another French pioneer, De Dion Bouton, Panhards were some of the most popular cars in the world before the fallout from the global recession of 1907-08 and the advent of the Model T shifted the big numbers to the burgeoning U.S. market.

The global influence of the brand greatly diminished after 1919. Panhards were still highly respected cars, and evolved into proper luxury machines. They were large, opulent, and powered by “silent” Knight sleeve-valve engines for quiet, smooth operation. But market share outside of France and the Low Countries gradually fell away.

A radical new car, 1936’s Dynamic, an innovative car with centrally-mounted steering and wild streamlined styling by Panhard’s chief designer Louis Bionier, did not remedy this situation. Only ~2,700 Dynamics were made before the war brought assembly at Porte d’Ivry, then a second facility at Tarbes, to an end.

If the war had not happened, Panhard might have slumped on a little longer – but things were not good for the manufacturer and many old-line French names had already faded away in the 1930s, including De Dion, which stopped building cars in 1932.

Le Plan Pons and J.A. Grégoire

In the 1930s many Government ministers under the Albert Lebrun government (the last of France’s 3rd Republic) wanted France’s car manufacturers to rationalize and modernize as France’s small makes and fragmented industry were hard pressed to compete internationally, aside from Citroën and Peugeot. The 50 or so French makes had little appetite for this, and there was no political leverage to make anything happen.

The interruption of the war, the bombing of many factories (including Porte d’Ivry), and the fall of the Vichy regime allowed for a proper industrial plan to be formed by the nascent 4th Republic Government. Robert Lacoste, the postwar minister of industry, assigned Paul-Marie Pons, a former Naval engineer and civil servant, to devise a plan to reconstruct the badly damaged infrastructure of the French Auto Industry.

The Plan Pons envisaged a consolidation of makes in both cars and trucks, with concentration on the volume producers. The hallowed names of luxury and sports cars were not part of the agenda. Under the plan, Panhard was meant to sync up with Simca, Fiat’s French licensee.

The plan didn’t really work out as anticipated, but for Panhard there was no other way forward. As early as 1942, the company understood that in the postwar era it would need to build a small, simple, and cheap car – and Bionier and engineer Louis Delagarde began working on one at the direction of Jean Panhard (son of the founder). Not far away, so did Jean-Albert Grégoire.

Grégoire was already a legend, having developed a variety of innovative front drive cars starting with the Tracta – first a race car and then a production car – in 1926-27. He was co-inventor of the CV joint. His work had spread, via license and consulting, to other manufacturers – Donnet, Chenard-Walcker, and finally Amilcar, which built his innovative, lightweight, front-drive Amilcar Compound in 1938-39.

The Compound used body panels made of Alpax – an aluminum alloy, and it was here that he forged a relationship with Aluminium Français. Like Jean Panhard and his team (and a similar group at Renault), Grégoire could see the postwar world of austerity already. His proposed light car would be small and front drive, and built in Alpax to save weight and fuel. He got Aluminium Français (AF) to help pay for building prototypes.

The car Grégoire developed, the A.F.G., was a lightweight, efficient front-driver. The exact kind of car Bionier and Delagarde were working on, except built in Aluminum and at a far more advanced stage of development. Grégoire’s car was almost production ready, Panhard’s was not. With the advent of the Pons plan, a constellation of political factors came together.

Both Panhard and AF could gain political points by working together to build the A.F.G. in concert, and Panhard, though it would need to heavily modify the car, recognized how much more expedient it would be to use the A.F.G. instead of spending potentially two more years ironing out their own car.

They would not have been allowed by Pons to produce the old style of Panhard cars, and Pons wanted the A.F.G. built. Building the car in Aluminum (with some steel sections) also expedited production – steel was hard to get in the 1940s, Aluminum, with airplane production greatly reduced, was not.

The design was also offered to Simca, who hemmed and hawed but chose to keep making the Cinq, a Fiat Topolino in French drag.

The “A.F.G. Dyna” was first shown at the 1946 Paris show, but the production car did not arrive for some time afterward.

The basic A.F.G. design was also developed in the U.K. as a car called the Kendall – which never got off the ground, and subsequently in Australia as the Hartnett – though neither venture really worked out.

Dyna X

Bionier and Delagarde merged their own ideas with the existing A.F.G. structure, much to Grégoire’s chagrin.

The car was made larger so that it could be wider and accommodate four doors, and was given a much larger flat-twin designed by Delagarde than Grégoire had imagined. The engine was mounted ahead of the front axle instead of behind as on the A.F.G. It also incorporated more steel to make the structure stronger, though the body was Alpax. Van and wagon (er, Break) versions were also designed.

The resulting car, the Panhard Dyna X (named to reflect the heritage of the prewar Dynamic), was finally on sale by 1948.

Grégoire hated the Dyna X, but part of that might have been that because the car was so extensively modified, Panhard had at first refused to pay him royalties on it and never acknowledged his role in the car. Litigation solved that, but in later years he referred to the Dyna X derisively. “When you see a Dyna on the road, it resembles a sister of the AFG… but a sister who suffers from cellulite.”

That said, the Dyna X was the only thing that got Panhard cars built after WW2 and it was a modest success for the company. Almost 50,000 of the cars were made into 1954.

The Dyna X was a luxury car but it wasn’t cheap – it cost about 40-45% more than a Renault 4CV, and so it’s appeal was to middle class customers – but it was highly unconventional for such a car.

Power came from Delagarde’s punchy flat twin, 745-cc from 1950 and 851-cc from 1952. It made more power than larger displacement fours from VW or Renault, but a two-cylinder car was always a marketplace handicap. It’s tall, upright styling was also a point of controversy – it didn’t look prewar, but it aged quickly.

It was also aerodynamically poor, which led Bionier to reclothe one in a radical streamlined body, the wind-tunnel-tested 1948 Dynavia show car. It could return 47 mpg at 80 mph from just 610-cc and was quieter and more stable than the production Dyna too. This led Bionier to begin working on a streamlined successor to the Dyna X – which became 1954’s Dyna Z.

Dyna Z and the Aluminum Problem

The Dyna Z was designed in roughly 1951-52, becoming production ready and bowing in the summer of 1953 – though it did not go on sale for some months. At that time, the cost of Aluminum was still quite low, so the car’s radically redesigned shell was built in Aluminum-Magnesium alloy, with less steel than before.

The Dyna Z retained much of the X’s basic layout but was all new with a fantastically futuristic, almost symmetrical body, the development of which Bionier had help with from Aluminium Français and designer André Jouan. The goal was longer, lower, and wider – making the car both more stylish and larger to sit in. It had a seventeen inch (43cm) longer wheelbase, was two and a half feet longer overall (180”/457 cm), and was nearly eight inches (20cm) wider than the X.

Theoretically the Dyna Z was a six seater, though in reality that would be a real squeeze.

It was as avant garde inside as it was outside. The much larger interior was complemented by a wild dashboard in which most of the controls and instrumentation were fitted to a huge binnacle that also served as the steering column. All Bakelite and Buck Rogers futurism. Everything was designed to be efficient, although you definitely needed to read the manual before heading out on the road.

The flat twin remained, but with the aerodynamic advantages of the new body, the car was quite a bit faster than the old X, weighing only 1,570 lbs. And with 40hp.

The 5CV rated car (important in the punitive displacement-based tax system in France) provided as much room as an 11CV Citroën and reasonable speed for a two-cylinder car, but again some customers balked at paying as much for the twin as the “proper” Traction Avant. Even if Panhard had wanted to design a new engine, the funds would soon be lacking to do so.

As Jets took over from surplus propellor planes, the cost of aluminum began to rise in 1953 and again in 1954 as Dyna Z production commenced in earnest. By 1955, it cost almost three times as much to make the car out of aluminum as it would have if it were bodied in steel. The company had also miscalculated the waste cost of the unused aluminum, which made the efficiencies even worse.

Having just spent a small fortune on a new Aluminum shell and not having properly costed it, the material costs of the Dyna Z very quickly began to eat away at any profit Panhard was making on the new car. Within months it was looking for a partner, and in April, 1955, Citroën took a 25% stake in the company – around the time the Dyna Z was hastily reworked for steel bodies.

Having invested in aluminum-stamping tooling, the heavier gauge of metal had to be retained, and the steel bodied Dyna Z was 200-300 lbs. heavier than the original. At first, aluminum was retained for some of the outer panels, but even those were gradually weeded out for cost.

In the four years between the launch of the Dyna Z and the true transition to steel, insurance companies had also discovered what collision repairers in the 2000s found – aluminum is hard to repair, which also hurt taxi sales, a traditional Panhard stronghold.

For Citroën, the Panhard range would theoretically slot nicely between the 2CV and the DS. For Panhard, access to Citroën’s much larger distribution network might equate to more sales – and certainly for adventures overseas this was very much the case. Until 1957 Panhard’s U.S. distribution was via a private importer in Los Angeles. After, it was handled by Citroën themselves in New York.

Panhards were just a little too weird for most U.S. consumers, and the two-cylinder problem was even more acute in the land of V8s, but Panhard integrated a great deal of American style into the existing Dyna Z design over time. The cars were brightly colored, sometimes with multi-tone paint jobs that resembled Detroit thinking in many ways. Detroit’s influence would be even stronger in the next Panhard.

PL 17

With all the issues with the Dyna Z (which included some early quality control glitches), Panhard set about reinventing the car for 1959, under the increasingly heavy hand of Citroën boss Pierre Bercot.

The new car got a new name – PL 17. The PL stood for Panhard et Levassor (a name nobody used anymore but which was still stamped on the ID plates) and the 17 for “5CV + 6 Seats + 6 liters fuel consumption (over 100km).” It was conveniently a smaller number than DS19.

The car again used the big flat twin, now with hydraulic valve lifters for quieter operation and in two states of tune – the regular 42hp 851-cc and the hotter cam 50hp “Tigre.” In 1960, the engines were reduced just slightly to 848-cc but now made 50hp and 60hp, respectively. That was to keep from running afoul of tax regs for cars above 850-cc, but had little effect on the cars themselves.

With lightweight bodies now out of the picture, Bionier returned to streamlining the cars. They got more ornamentation and more Detroit-like styling, sort of, but supposedly had a drag coefficient of just .26, which probably made them the slipperiest cars of the 1950s and allowed them to keep an 80+ mph top speed.

As with the Dyna Z and Dyna X, lots of thought was given to ways to keep the car light. The lightweight wheels had no centers – instead, they bolted directly to the brake drums for less unsprung weight, sometimes with hub caps to hide this setup, sometimes not. As before, the four-speed transmission, sans syncrho on first gear, was shifted from the (huge) column.

The suicide front doors of the Dyna Z were at first retained, then soon gave way to regular doors, and the interior also got a refresh and some redecoration. In this period you could order your “Tigre” with an actual Tiger-print interior from the factory, if you bought the “Grand Standing” model, the top-spec.

Estate and Cabriolet versions of the PL 17 were offered – but they were essentially coachbuilt cars. The convertible was a holdover from the Dyna Z range and was designed and built by Albert D’Ieteren in Belgium – it was updated for the PL 17 changes with production eventually moving to France on a limited basis.

The break, which had a long wheelbase but the same overall length as the sedan, was developed in Italy by a company called Panauto, then brought in-house to France, replacing the convertible on the production line but still being built in relatively small numbers. Both cars were a tiny fraction of PL 17 production.

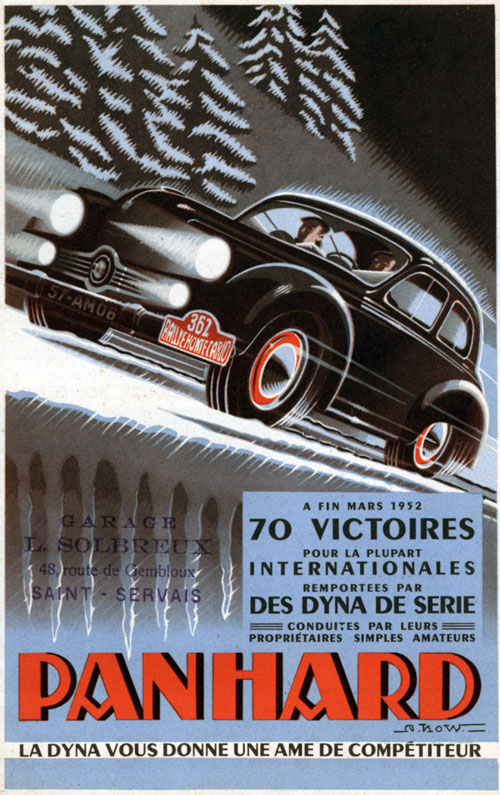

Both the Dyna Z and the PL 17 were quite popular in competition because of their relative power to displacement. A VW 1300 had a far bigger engine but much less speed, and the 850-cc limits meant that Panhard engines were a favorite in some small sports cars. Panhard even produced its own – the Dyna Junior – from 1952-56. The engines also powered the highly successful Deutsch-Bonnet and later Panhard CD racing sports cars.

This racing success did not translate into bigger sales, and though the PL 17 was a decent seller for what it was, it never managed to move more than about 35,000 units a year. That was not really enough to keep Panhard afloat forever even with Citroën’s help, and the relationship with Quai de Javel also came with constraints.

Citroën did not want Panhard to develop a car to compete with the Ami or the GS, but those projects were repeatedly delayed. Instead, to have something new, the partners agreed that Panhard should develop a new Coupe. The result was the achingly pretty 24BT/CT, designed again by Bionier with Jouan and now also René Ducassou-Pehau, who had been a staffer on the PL 17 restyle as well.

The 24 was a gorgeous car, but Citroën did not, as was suggested early on, allow Panhard to use the DS’ four-cylinder engine in any version of the car. The 24 had an all-new shell, but re-used many parts from the PL 17, which was by then winding down.

The PL 17 continued in production into 1965, by which time the design had run its course despite modest updates in 1963 to keep it fresh. That same year, Citroën took over Panhard entirely – mostly to gain factory space – Panhard was already building 2CVs on contract, a history which eventually led to the Citroën Dyane.

The 24 lingered another two years, but the last Panhard car was built in 1967. Panhard’s defense business, which had evolved separately from cars since the 1930s and was separate from the car business after the Citroën takeover, was still going strong, and continued to exist in various forms until 2012.

This PL 17

This particular PL 17 is owned by enthusiast Paul Melrose, who’s hosted many events that Old Motors has attended. It is a 1960 Tigre, and a rare example of a stateside Panhard. The make was never all that popular in the USA, but did manage to make some headlines in the roughly 1957-1961 era, before Detroit’s compacts pushed out “mid size” foreign cars for awhile.

The Panhard’s strange styling and highly unconventional nature also limited its U.S. marketing – fuel costs weren’t so important to Americans and two-cylinders was six too few for many. Panhards were imported to the USA into roughly 1962, though you could still privately import one afterward.

Pingback: The Rally of Monte Carlo, a world competition : The World In Stamps