Today the Toyota Sports 800 seems so different from the kinds of cars Toyota is largely famous for that it’s hard to believe the same folks who came up with the Corolla also designed it. But that’s literally the case—Tatsuo Hasegawa, the same engineer who led development on the original Corolla also largely designed the Sports 800. And the ingredients beneath its exotic exterior were entirely plebeian, sourced from the lowly Toyota Publica.

To make the magic happen, Hasegawa & Co. took a page from Colin Chapman: “Add lightness.” In feel and concept, the Sports 800 was very much like the Lotus Elan, sans fiberglass. Lightness was a quality inherent in the parent car and the Sports 800 was not so far removed from it, but the visual and experiential transformation into the Sports 800 could not have been starker.

Dubbed the “Yota Hachi” by fans in Japan, Sports 800 was Toyota’s first sporty car of any kind and along with the Datsun Fairlady and Honda S-series, one of the earliest Japanese sports cars. Though the prototype for the Sports 800 was shown in 1962, an actual production version didn’t arrive for three more years. By then, Honda had launched the S500 and Datsun was on its second iteration of the Fairlady roadster.

Falling between them in size, while the Sports 800 was closer in concept and displacement to the Honda, it wasn’t quite like either one of them.

The “Public Car”

The original Publica debuted in the summer of 1961, six years after Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) put out a call for a “national car.” The idea was meant to stimulate competition between Japan’s fledgling automakers to produce a car that a broad spectrum of Japanese consumers would be able to afford and actually want to drive.

Like the Kei car class, it took a while for actual cars to appear because the brief was pretty tough – it had to weigh less than 882 lbs., get 71 mpg, cruise at 60 kph (37mph) and have a top speed of over 100 kph (62 mph). Oh yeah, and it couldn’t have a breakdown for 100,000 kilometers (62,000 miles) – so it had to be simple. Though more famous now for the Corolla and other models, Hasegawa was also the lead engineer for the Publica, and it was he who was primarily tasked with figuring out how to build such a car.

At first, Toyota was inspired to produce something similar to the Citroën 2CV, which fulfilled pretty much the same role in France. But engineering the front-drive setup proved too complex, and while MITI indicated there would be tax incentives for keeping the car under 500cc, there just wasn’t enough power in a four-stroke 500cc engine to meet the performance goals.

The engine, still to be an air-cooled flat twin like the 2CV’s, was bumped up to a ceiling of 700cc but would be mounted in front and drive the rear wheels.

The U-10 Publica, whose name was roughly “Public car” although in Japanese it sounds suspiciously like “Paprika,” debuted in the summer of 1961. It did everything it was supposed to – it was reliable, cheap, capacious, and basic. Too basic.

At first, the Publica came only as a 2-door sedan and almost everything was an extra – including a radio and a heater. It was bare bones inside and while it drove pretty well – a nice double-wishbone front suspension made it very competent – it wasn’t anything exciting.

The car’s arrival coincided with a serious acceleration of consumer demand for cars during the time of Prime Minister Hayato Ikeda. Elected in 1960, Ikeda proposed a doubling of income for Japanese workers by the time of the 1964 Tokyo Olympiad and given the prodigious rate of economic growth – in part stimulated by building cars and motorcycles – that seemed realistic.

Hasegawa soon realized that people would want more than the basic Publica, and the car was continuously upgraded to suit. The origins of the Corolla also lay in consumer reactions to the Publica. They viewed it as lacking some very basic livability features. While the Corolla was some years off, Hasegawa and managers all the way up to Eiji Toyoda recognized the need to hook more customers quickly.

Their short-term answer was to make a sporty, cool version of the Publica that had none of the image of a stuffy “public car.”

Publica Sports

To do that on the cheap, Toyota enlisted the help of Shozo Sato, a Nissan designer on long-term leave due to health problems. It isn’t really clear if Sato was still working for Nissan at all by 1962.

He’d joined Nissan in 1937 and by 1950 was essentially the lead designer. Sato oversaw the design department until at least 1959, and most of the Nissan cars introduced before 1961 had some of his input. He won the 1956 Mainichi Design Award for his work on the landmark 112-series Datsun Bluebird and was fond of quickly working up oil paintings of his favorite cars right there in the studio.

A supreme artistic talent and a driven perfectionist, his insistence on doing things “the right way,” meaning his way, may have irritated his superiors and engineers in the company.

Sato was not shy about speaking his mind if he felt a decision was the wrong one took an unusually freewheeling tone with his superiors if he thought he was in the right. Meetings often saw him return to the studio in fits of rage, or long periods behind a locked door.

A heavy smoker even by the standards of 1950s Japan, Sato was sidelined by several bouts of ill health in the late 1950s. Even when he was out of the office an engineering colleague dropped by his apartment every day to pick up copious notes and instructions. He could be a micromanager, but was also self-deprecating and funny, once remarking to former underling Isao Sono, who went on to be one of Nissan’s top designers in the 1970s and 1980s, “’I’ve heard that I’m the worst-performing section head in the entire company. I wonder if it’s true.”

By the end of 1959 he was out on leave again, likely for good.

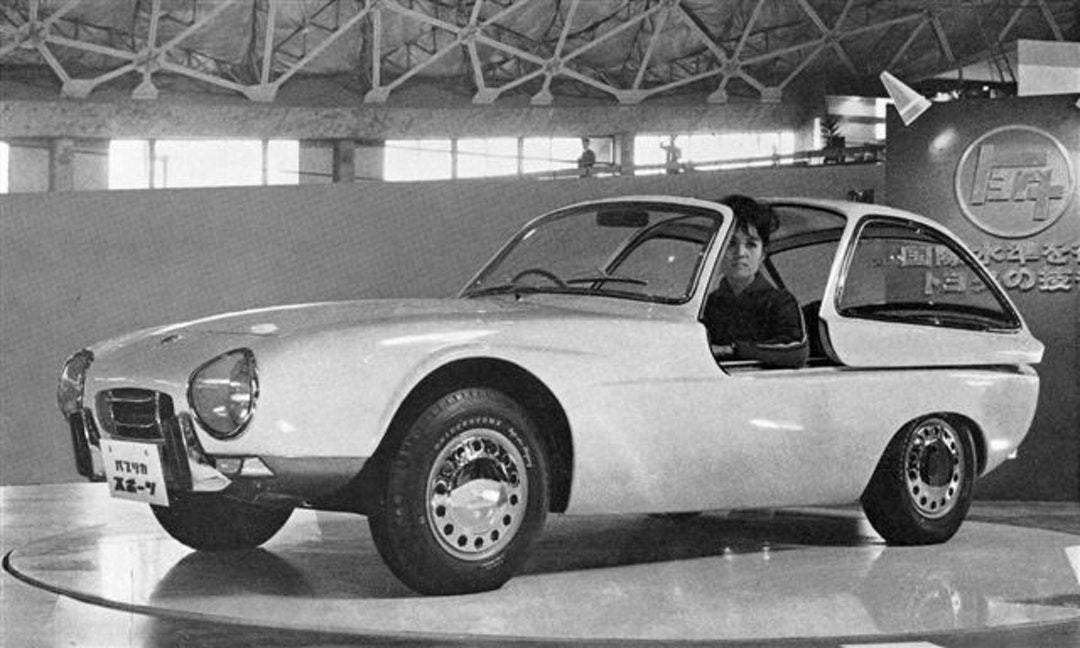

Sato worked with Hasegawa to create a re-bodied Publica for the 1962 Tokyo Motor Show, which became the “Publica Sports.” It’s not clear who sketched what or how it evolved, but the sleek coupe wrapped around the existing mechanicals. It was much lower and far more radical.

The space-age concept didn’t have doors or a roof – it had a bubble roof that slid backward on rails and two comfy seats in the small interior. Showgoers loved the car and Toyota got to work on making it a reality as a result.

Sato’s involvement after that is unclear. He spent many more years doing his beloved oil paintings and watercolors for the Japanese magazine Car Graphic under the pseudonym Imitatio Cecili, also writing a regular column about vintage cars, but he never helmed another major design.

Sports 800

The production Sports 800 didn’t appear for almost three years – a long time for what was supposed to be a simple reskin of existing mechanical pieces.

Months before the Publica Sports, Honda had shown the S360 at Suzuka Circuit. Honda dealers loved this exciting little Kei roadster and so did the public, but Soichiro Honda wanted more out of it than a Kei car. At the Tokyo show that fall, across the hall from the Publica Sports, Honda’s lineup of cars was born when the expanded S500 was shown alongside the original S360 prototype and the T360 truck.

Though dimensionally a Kei car, the S500 wasn’t part of that class; its engine was over the 360cc limit. But it was still tiny and light – and exciting. The S500’s itty-bitty twin cam four pushed out a whopping 44hp from just 531cc, revved to infinity, and weighed just 1,500 lbs. It went into production months later and put Honda on the map as a car manufacturer, but it also dealt a severe blow to the Publica Sports.

The sliding roof of the Publica Sports was exciting but very heavy. The Publica’s 28 horses were no match for that extra weight and certainly not enough to be competitive with the S500, so the concept needed considerable reworking under Hasegawa’s direction.

The lines were refined to be more aerodynamic but kept most of the spirit and shape of the original. Hasegawa had been an aircraft engineer before and during WW2, and engineering the Sports 800 must have been like revisiting his old job – the principle was the same – save weight.

Just about everything that could be made lighter or eliminated was, starting with the sliding roof. Conventional doors and a targa-top arrangement replaced it, which also helped add structure to the lightweight body. If it had been a pure roadster, it might have been a flexible flyer.

The top, which stowed in the trunk, was made of aluminum to save weight. Aluminum was used in several other areas, like the seat frames, and thin-gauge steel was used throughout most of the unibody (many Sports 800s later rusted away to dust).

The engine was punched up to 790cc and 44hp, and labeled the 2U-B, which was also eventually used in the regular Publica. It came only as a four-speeder.

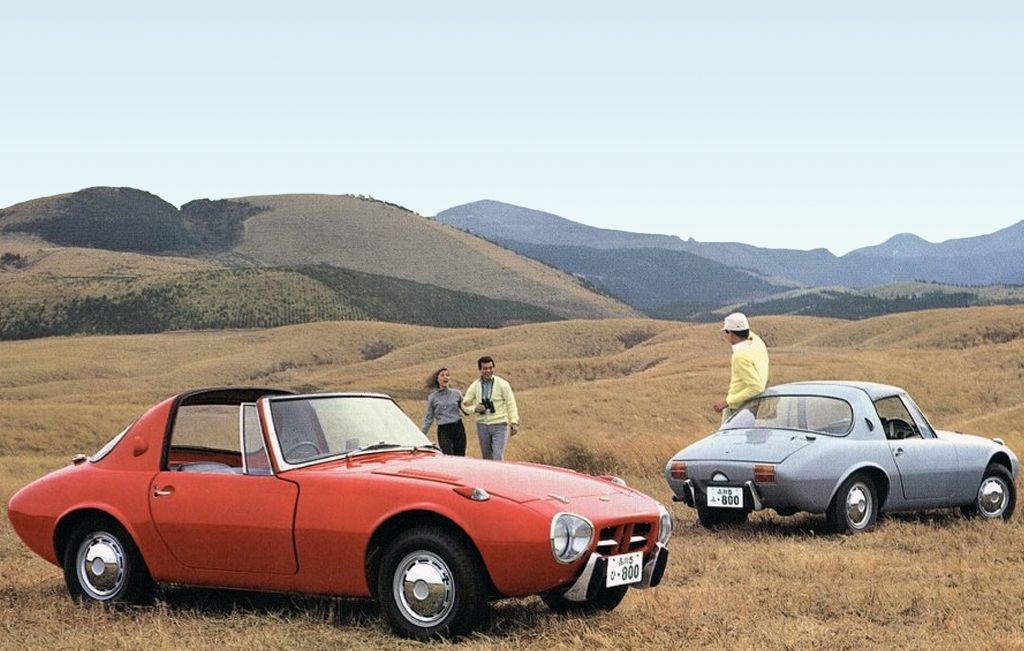

That was not as much power for the size of the engine as the Honda, and it didn’t rev as high, but the 141” (356cm) long car weighed just 1,280 lbs. and was shaped like a bullet, which meant it could eke out a 96mph top speed and had electrifying handling.

Never meant to be a big volume car, Toyota did not build the Sports 800 itself. Instead, it contracted out production to Kanto Auto Works in Yokosuka. Production began in the spring of 1965, and the car was cheap at just ¥595,000 – but your lifestyle had to suit a tiny two-seater.

The Sporting Life

Just 3,131 Sports 800s were built at Kanto into the fall of 1969, and almost all of them were right-hand-drive cars meant to stay in Japan. The car was also built in left hand drive for Okinawa’s American customers, and 40 left hookers were shipped to the USA in 1965 for test marketing.

American dealers didn’t think there was much potential in the tiny car and turned it down, despite Datsun’s increasing success with the Fairlady 1600 roadster. Amazingly, Toyota let them sell off the 40 cars to the pubic rather than ship them back to Japan, something regulations would have prohibited by 1968.

In 1966-67, Toyota took the car racing in Japan, in the latter year alongside its big brother the 2000GT. Because the tiny, aero-optimized car could return 73 mpg, it proved a capable endurance racer. Good performances at the Fuji 24 hour and other races didn’t seem to generate consumer interest.

That had more to do with the fact that even in a wildly expanding economy, two-seat sports cars were of limited use outside of track day fun. The Sports 800 was even more of a toy than the Datsun Roadster or Honda S-series, as it lacked any real luggage space. Even in booming 1960s Japan second cars were unusual.

The small numbers eventually meant that finding parts for the 800 was not easy – even in the mid-1970s, many parts were already unobtainable, a situation that’s even more acute now. A close knit-group of clubs and enthusiasts help keep the survivors – about 10-15% of production – on the road and track.

Though production ended in 1969, the 800 mysteriously appeared a decade later at the 1979 Tokyo show. The light weight of the car made it a good template for a prototype hybrid car – which hooked a small gas turbine engine to an electric drive system. Nothing came of this prototype, but the Sports 800’s platform was used again for a pair of full EV prototypes in 2010.

By the time the Sports 800 reached production in 1965, Toyota had begun collaborating with Yamaha on the exotic 2000GT – a true halo car meant to be Toyota’s equivalent to an XKE or a Maserati Mistral.

These two cars were the original sporting Toyotas, but their formula was distinctly “niche model.” The company watched closely as Ford created the Mustang out of ordinary sedan pieces, then Fiat did something similar with the 124 coupe, and then Ford again created the Capri out of the Mk2 Cortina.

With Japanese buyers flocking to flashy hardtops that were ‘sporty’ but could double as family cars, Toyota applied the Mustang/Capri formula to the Corona and begat its first truly successful sporty car – the Celica. It arrived about a year after Sports 800 production ended.