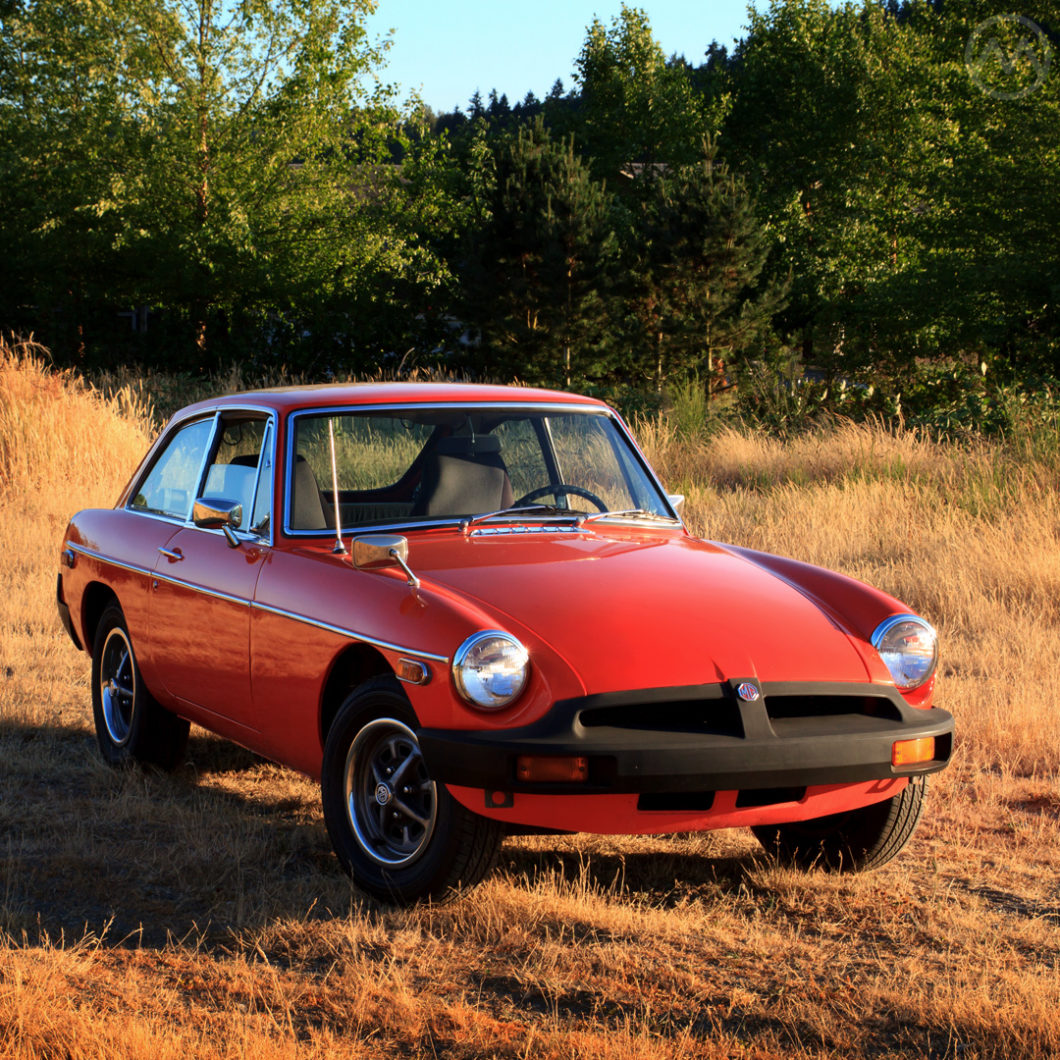

Today’s car is our very own 1974.5 MGB/GT. I hear you asking, “point five?” Yes. Typically, new models are launched in the fall that precedes the calendar model year – but that was only partially possible for the 1975 MGB. The “1974-and-a-half” cars were a regulatory creation because British Leyland had not yet federalized the fuel and emissions components that would make the 1975 cars emissions compliant in the U.S.

So it was that for about three and a half months, from September to the end of December, 1974, MGBs came with 1975’s body and chassis changes, but 1974’s engines. According to former British Motor Heritage Trust archivist Anders Clausager, 7,445 such cars were built. Unsurprisingly nearly 90% of them were for North America – by far MG’s biggest market.

The entire story of the infamous “rubber bumper cars” centers on American requirements. Automakers don’t go through the kinds of contortions British Leyland did for these cars if it isn’t worth their while. Case in point? Citroën, who decided the expenditures needed to deal with new DOT and NHTSA requirements wasn’t worth it given its tiny sales volumes and eroding financial situation, and departed the USA.

The most visible part of this tale were the changes needed to meet “FMVSS 215” – the actual legal standard for bumper protection enacted in 1972. Many people derided the “Rubber bumpers” (they’re not actually rubber), but the MGB enjoyed very good sales even after the 1975 changes blunted the performance of the car. MG sales in the USA were as strong in 1977 as they were in 1970.

But that’s only part of the story. All of the MG’s sold in North America after January 1, 1975 were roadsters. The fastback MGB/GT, though it continued in production at Abingdon with the roadsters until 1980, was dropped from the USA when 1974 came to a close. Just 1,248 “rubber” bumper GTs made it to North America and some didn’t even reach the dealer until early 1975.

That February, one reason (but not the only one) for the departure of the GT became clear when the Triumph TR-7 debuted at the Chicago Auto Show. It’s creation, too, was the result of American legislation – or the possibility of American legislation.

The Legislators

The root cause of the entire “impact bumper” era lay in consumer complaints about the increasing fragility of primarily American cars when it came to cosmetic damage, and those complaints were usually directed at insurers and consumer advocates.

As early as 1968 congress had hearings on how to alleviate the out-of-pocket costs of fixing minor fender benders, a consequence of congress taking a look at more substantive automotive safety issues and beginning to require safety equipment and establish safety standards. It was the insurance industry that directly lobbied to have bumper protection standards enacted, but their argument was bolstered by consumers who complained that even a mild parking bump in a 1970 Mercury Montego, with its pointy prow and frilly grill work, might cause many hundreds of dollars in damage.

In 1966, President Lyndon Johnson appointed Dr. William Haddon Jr. as the first administrator of the then-new National Traffic Safety and National Highway Safety Agencies, which were later combined into the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA).

Haddon was primarily interested in saving lives but was also pragmatic – he drew criticism from Automakers for excessive regulation but also from consumer advocates for not being sufficiently zealous in regulating automakers. He eventually departed for the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety and there he studied the costs associated with these minor accidents. They were more wallet costs and less “human costs,” but still, Congress could see the data and hear the complaints.

Hitting something in a 1970 Mercury Montego at 5mph? It’d do roughly $275 in damage, equivalent to almost $1,800 in 2020 dollars. Haddon’s studies found that about 1/3rd of motor vehicle accidents fell into this “needlessly expensive” category.

After a long period of debate, two members of Utah’s congressional delegation – Representative John E. Moss and Senator Frank Moss – both took up Haddon’s cause and helped craft the legislation that mandated better bumper protection standards. Neither were strangers to public advocacy. John E. Moss was a key architect of the Freedom of Information Act. Frank Moss had helped craft Medicaid and the Clean Water Act. There were also other sponsors for new solutions, such as Washington’s Warren Magnusson.

That year NHTSA issued a host of updated rules, including a host of updated standards including FMVSS (Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard) 215 – the “Exterior Protection Standard.” This particular rule meant that any new car sold in the United States had to be able to withstand certain impacts without serious damage or damage to the required safety lighting on the vehicle.

The standard began with the 1973 model year – 5-mph in front, 2.5 mph behind, as studies showed more accidents involved front end damage. From 1974, it was 5-mph front and rear with 3mph corner standards added. The bumpers had to be at predetermined heights to protect from common impact areas. Headlights were also required to be at a certain height. Additionally, there was also a roof-crush standard, FMVSS-216, though convertibles were excluded. Congress codified the rules in 1972.

The predicted savings to consumers by 1980? $4 Billion. That actually did happen; later studies found that bumper-related insurance claims on one-year-old cars dropped from almost 60 percent of claims in 1972 to less than 40% in 1976 and that claims were lower in cost, too.

The changing regulations, which had greatly increased in scope from 1966, did not present an easy environment for car companies; particularly ones with as many issues as British Leyland.

British Leyland’s Best Laid Plans

After the formation of British Leyland in 1968, there were several plans for new sports cars on the drawing board including proposals from Triumph and MG. MG’s ADO21 was a mid-engined car that looked a little like a Lombardi Grand Prix. Triumph’s “Bullet” was a conventional front-engine, rear-drive proposal that looked a little like a front-engined Porsche 914 and had a similar targa-top arrangement.

MG’s ADO21 used almost nothing from the corporate parts bin aside from a hydrolastic suspension, and for cost reasons it was not pursued. Instead, Triumph’s car was developed into a new “corporate sports car,” which became the TR-7, with the potential for an MG variation. BL was run by people who tended to favor Triumph, despite MG’s better market position. Needing to allocate its resources to new family cars, BL only had money for one new platform. As early as 1970 the Triumph project was in motion.

The MGB turned ten years old around the time the new NHTSA rules were issued, but it was still a good seller. The inclusion of the roof-crush standard and the rapid evolution of the safety regulations over the previous six years led many car companies to conclude that the future of convertibles might be in doubt. The MGB would hold on until it was no longer viable or legislation killed it while the targa idea for the TR-7 was abandoned in favor of a fixed roof.

If the TR-7 was aimed at the future, there was still the matter of the present for Abingdon to deal with. To keep the B on sale, it had to meet bumper and emissions standards. The first solution to the bumper problem was the “Sabrina,” named for the, er, assets, of fifties British Pinup Girl and actress Norma Ann Sykes.

The actual “Sabrinas” were huge metal and rubber overriders mounted to the front chrome bumper of the 1974 MGBs, replacing smaller overriders from 1973.

Many owners removed them almost immediately (indeed, a Sabrina-equipped ’74 is a very rare sight today), but they made the car compliant at time of sale – if only briefly. To deal with the corner and height standards long-term, more substantial changes were necessary.

The “Rubber” Bumpers

The MGB was now more than ten years old, with a body structure designed in the late 1950s. Getting it to the point where it could sustain a 5-mph impact with virtually no damage would not come without a cost. Figuring out how to do it, however, were two people who knew the MGB very well – engineer Roy Brocklehurst and body man Jim O’Neill.

Brocklehurst served as a liason to the federal authorities, but no amount of describing the difficulties of adapting the car would earn it a reprieve. The bumpers would need to be beefy steel items supported by additional mounting structure. By late 1972 there were two options – a big steel arrangement that looked sort of like the impact bumpers Porsche put on the 911, or a steel setup encased in black plastic that looked far more aerodynamic.

Most American car bumpers of this era, Brocklehurst later stated, were mounted on impact absorbing shocks. To take the same approach on the MGB would mean mounting a big rail very far out in front of the car and very high up, which wouldn’t ever look right.

The latter option was designed by O’Neill and Harris Mann, the stylist who designed the very different TR-7 then in development. O’Neill credited Mann with the look, and the engineering team with making it work. The final bumpers were Marley Foam over steel with a urethane exterior. This plastic material was the only one that would work in the huge temperature range of the 50 states.

Early on, the team experimented with painting the bumpers – which some MGB owners have done in subsequent years – but found that it was hard to make paint stick to the surfaces without using toxic chemicals. In the end, all would be black. They looked and seemed to function like rubber, which is how they got that name, but they were plastic.

Purists hated the new bumpers – but in hindsight, they were a far more elegant solution than the ladder-like appendages on the Fiat X1/9 or the blunt, rail-like pieces on many American cars, and they were effective and hard wearing. They were very color-dependent too – some colors looked great, others dull with the new treatment. A less sculpted version was applied to the rear of the car. O’Neill did not think the treatment was too bad, Brocklehurst didn’t care for it.

To make them height compliant, the front suspension was raised, and the added weight of the bumpers did nothing for performance, already strangled by increasing emissions regulations. Speaking of which, the existing twin-SU setup of the MGB, though it had been modernized since the early days and now consisted of HiF-4 carburetors, would not pass 1975’s emissions rules.

With little time or budget to deal with that, the ‘74.5 solution presented itself as a temporary reprieve. Impact bumper cars began rolling off the line in September.

The late MGB/GT

The weight of the bumpers, according to Brocklehurst, put the GT into a heavier class of car than the roadster despite the fact that it was only about 50 lbs. heavier, which he later said meant having to do even more work to make it emissions compliant. That might be true, but the GT was also an old product and BL had invested a huge amount of time and money in the TR-7, which was about to come online. It came only as a coupe, and the company was eager to ease it’s introduction.

The MGB/GT was thus dropped from North America at the end of calendar year 1974, though sales of late deliveries continued into the early spring. 1975 MGBs were fitted with a new carburetor – a single Zenith-Stromberg CD175, which made it clean but not as powerful as before. There were more changes, too, mostly small mechanical tweaks.

How to tell the ‘74.5 from a later car at a distance? The ones built in 1974 have a red MG log on the front bumper, while later cars have a black logo.

That February, the TR-7 appeared at the Chicago Auto Show amid a huge PR campaign – “The shape of things to come.” At first, TR-7s were exclusively built for North America. Triumph fans clamored for an extension of the TR-6’s life and got one, at least for a year, but the TR-7 would eventually sell in larger numbers than any previous TR.

At home, the MGB/GT was still on sale and soon got a special edition, the 1976 Jubilee. The GT’s V8 variation, never offered in the USA, was built until 1976. Like the roadster, there were additional modifications over the rest of its life: a new dashboard, new seats, a chunky front anti-roll bar from 1977, and an LE edition in 1980 in different colors than the roadster. Unlike American models which seemed to rarely be equipped with overdrive, UK buyers in this late era seem to have chosen it almost every time.

In the U.K., the “rubber bumper” MGB/GT is a fairly common classic, but thanks to its brief window of availability, it’s very rare in North America.

MGB sales were strong into 1977-78, though they trailed off thereafter. By the end, of course, the car was very dated, and the rapid decline of British Leyland’s fortunes in the 1970s had meant there could be no direct replacement for the B. It was still an attractive car if one outclassed by newer competitors, particularly cars like the Toyota Celica – new in its second generation in 1978.

Locking the TR-7 into coupe form also held it back until 1979, when a roadster was finally unveiled. The potential rollover legislation threatened in 1971-72 never did materialize, and the early (and well publicized) teething troubles of the TR-7 meant by the time the roadster arrived, fewer buyers were interested than might have been in 1975.

Many owners later modified their “Rubber bumper” cars using the twin-carb setups of the earlier vehicles and/or stripping them of the heavy rubber bumpers. Another popular modification is lowering the front suspension – easily done with a set of pre-1974 springs.

great article